A Life Swept Away :A Tragedy of imtiaz Ahmad Magray

A Life Swept Away :A Tragedy of imtiaz Ahmad Magray

On the morning of May 4, 2025, the village of Tangmarg in south Kashmir’s Kulgam district woke to silence, one not of peace, but of grief. The body of 23-year-old Imtiaz Ahmad Magray, a daily wage labourer, was pulled lifeless from the waters of the Veshaw river. His death is now just another statistic for the authorities.

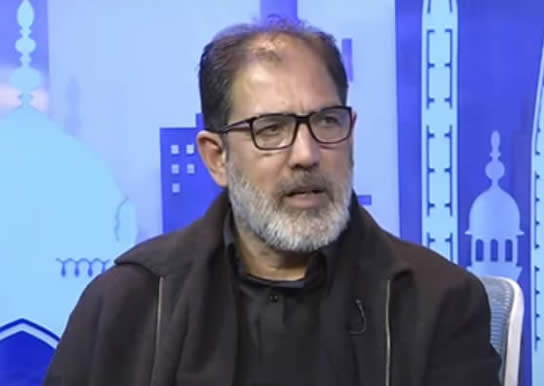

But to his family, neighbours and those who knew him, Imtiaz was not a suspect, he was a son, a brother and an innocent caught in the deadly machinery of suspicion and state force. A day earlier, Imtiaz had been picked up for interrogation. Police alleged he had fed and sheltered armed men in the forests near his home. Friends say he was terrified. He wasn’t a militant, they insist, he was a poor man with nothing but a worn-out shovel and tired hands. The kind of person who went out each day hoping for enough work to bring home rice for dinner.

According to official sources, Imtiaz "agreed" to guide the army and police to a supposed hideout in the woods. But something happened that morning. A video, circulated widely, shown Imtiaz pausing near the trees, looking around anxiously, before bolting toward the Veshaw river. Moments later, he hurls himself into the icy current. No one followed. No one tried to stop him. No voice is heard calling him back.He can be seen thrashing, struggling to stay afloat. But the river, cold, merciless, sweeps him away. Hours later, his body was found by local residents.

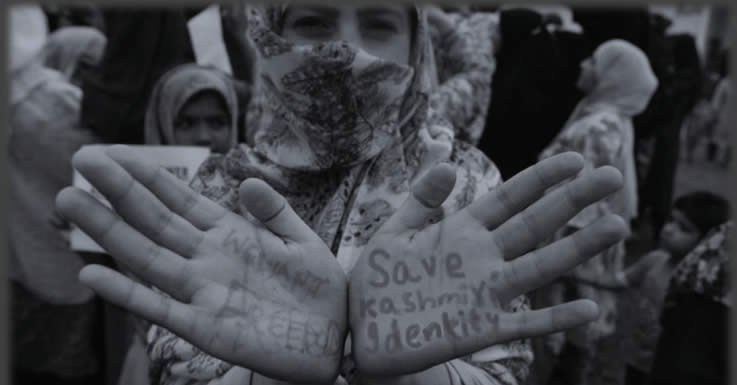

There was no rescue, no security personnel nearby when he jumped. Why was he alone? What led him to such panic? Was he running for his life, not from the law, but from what he feared might happen next? His family believes he was under immense pressure. “He was innocent,” said his father, Nazir Ahmad. “He was afraid. They threatened him. My son had nothing to do with what they claimed.” In Indian occupied Jammu & Kashmir, such tragedies are not rare. They are buried under official statements, vague terms, alleged, suspected and claimed. But for those who are left behind, there is only sorrow and questions that no one will answer.

Imtiaz did not have a gun. He had no charges against him. He had dreams, though small, that were his own. In a land where the line between innocence and guilt blurs at the whim of authority, Imtiaz was swept away, first by fear, then by water. His death is a wound on the conscience of a place that has seen too many. And like most such wounds, it will be denied, forgotten, rewritten. But in Tangmarg, a mother still waits for her son to walk through the door. A father still wonders if telling the truth to the police was their biggest mistake. And a river flows on...........carrying with it a life that should never have been lost.

Related Reports