Militarized Margins Human trafficking gendered violence and state complicity in occupied Kashmir

Militarized Margins Human trafficking gendered violence and state complicity in occupied Kashmir

INTRODUCTION

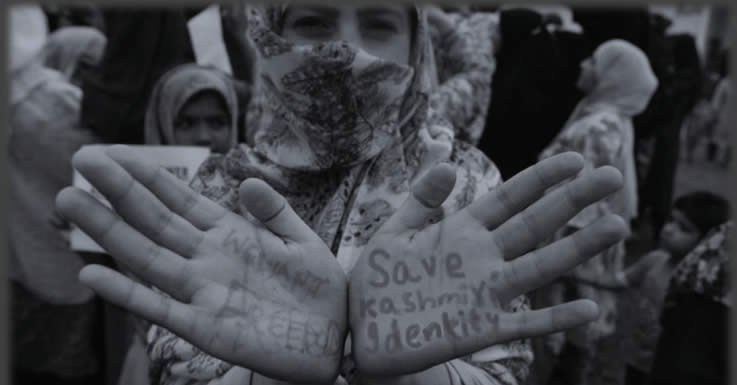

The political and security situation of Indian occupied Jammu and Kashmir has undergone significant transformation in recent years, particularly following the abrogation of Article 370 in August 2019. This legal and constitutional shift marked not only the formal erosion of the region’s limited autonomy but also intensified the regime of surveillance, securitization and demographic engineering. Under this newly engineered regime of control, women’s lives have become increasingly vulnerable to structural violence, forced disappearances and forms of exploitation including sex and human trafficking. These are not isolated incidents but symptoms of a larger pattern of gendered insecurity embedded in conflict governance.

Militarization in Kashmir is not merely a matter of troop presence, it reflects a broader logic of occupation. Checkpoints, night raids, surveillance, arbitrary detention and psychological intimidation operate as tools of coercive statecraft. In such environments, the line between national security and human insecurity is blurred. Women, especially in conflict-ridden geographies, suffer in both direct and indirect ways, as victims of sexual violence, as caregivers to disappeared men and as breadwinners in collapsed economies. Militarization thus becomes not only a territorial project but a deeply gendered one, regulating bodies, space and mobility.

Human trafficking in Kashmir is emerging as invisible yet critical forms of conflict economy. While official discourses rarely acknowledge this trend, recent data and investigative reports reveal a sharp rise in trafficking cases since the abrogation of Article 370 in August 2019. This constitutional change, which revoked the region’s limited autonomy, has been accompanied by massive political repression, increased paramilitary deployment and a breakdown in democratic institutions. It has also produced a legal vacuum, weakening protections for vulnerable populations, especially women and children. In this setting, trafficking has become both a survival strategy and a tool of exploitation.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), nearly 9,765 Kashmiri women and girls were reported missing between 2019 and 2021, three times higher than the preceding three years1. Activists and journalists report that many of these disappearances are not merely domestic or familial matters but are linked to organized trafficking networks, involving coercion, deception and in some cases, complicity of local actors and authorities. The Handwara sex racket busts in 2023–2024 provide empirical evidence of this trend. These developments align with global conflict patterns where women’s bodies become both symbolic targets and material resources in wartime economies.

The role of state institutions in this crisis cannot be ignored. India’s militarized governance in Kashmir operates through legal exceptionalism, notably the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA) and the Public Safety Act (PSA), which provide security forces with sweeping powers and immunity from prosecution. These legal architectures foster a culture of impunity, where violations against women are rarely investigated or prosecuted. Historical incidents like the Kunan-Poshpora mass rape (1991) continue to be emblematic of the state’s failure to deliver justice. In recent years, the disbanding of the Jammu and Kashmir Women’s Commission, delays in filing FIRs and police indifference toward missing persons’ cases have further eroded institutional credibility. 2

This paper investigates how the convergence of conflict, militarization, economic collapse and gender inequality enables the rise of sex and human trafficking in Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir. It critically examines the role of the state, as both regulator and violator, as well as the structural conditions that sustain trafficking.

This paper also examines the resurgence of sexualized hate against Kashmiri women following the Pahalgam attack, framed within the context of militarized violence and ethnic nationalism. It argues that online and offline hate speech, fueled by right-wing ideologies, reflects deeper structural violence and the weaponization of gender in a conflict zone. Through a multidisciplinary approach, combining case studies, policy analysis and legal review, the study situates the trafficking crisis within broader IR debates on state violence, gendered security and human rights erosion under occupation.

METHODOLOGY

The methodology is qualitative and desk-based. It draws from secondary data sources, including investigative journalism, human rights reports, court documents, media archives and existing academic literature. By situating the Kashmiri case within global patterns of conflict-related gender- based violence, the paper aims to shed light on a largely ignored dimension of the Kashmir conflict, where the body of the woman becomes a site of both political violence and strategic neglect.

DRIVERS OF HUMAN TRAFFICKING IN JAMMU & KASHMIR

Recent official data reveal an alarming surge in missing women and girls in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), underscoring deepening concerns about sexual exploitation and human trafficking in the region. As of mid-2023, India’s Ministry of Home Affairs disclosed that 9,765 females went missing in J&K during 2019–2021. This total included 1,148 girls (under 18) and 8,617 adult women. By way of comparison, national crime records show that over 13.13 lakh (1.313 million) women and girls were reported missing across India in the same three-year period.

While J&K accounts for only a fraction of that national figure, the trend locally is especially striking: the number of missing females in the Union Territory has roughly tripled since the previous three-year period (2016–2018)3. This section examines these statistics in detail, situates them in context and discusses official and civilian narratives regarding their causes and implications. Over three decades of militarization has hollowed out the legal, educational and welfare frameworks designed to shield vulnerable populations. In this climate, women have become primary targets of traffickers exploiting economic desperation, displacement and weakened familial structures. The Kashmir Valley, particularly districts like Kupwara, Pulwama and Anantnag, has seen an uptick in reported and suspected cases of trafficking since the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019.

The socioeconomic dislocation that followed further weakened the safety net for women.

• Economic deprivation is a central factor enabling this phenomenon. With thousands of men dead or disappeared, many women were thrust into the labor market despite low literacy rates, 58.01% for women versus 78.26% for men, forcing them into low-paying, unskilled work in handicrafts and agriculture. According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), Jammu and Kashmir had an unemployment rate of 18.3% in early 2024, among the highest in India.4 The situation is graver for women, many of whom lost informal sector employment in handicrafts and tourism due to militarization and the pandemic.

Widowhood and displacement further compound women’s economic vulnerability. A 2023 UN Women brief highlighted that over 35% of female-headed households in militarized regions like Kashmir live below the poverty line.5 This lack of financial autonomy makes women more susceptible to exploitative practices disguised as economic opportunities or marriage offers.

• Education gaps contribute significantly to the persistence of trafficking. Female literacy in rural Kashmir hovers around 56.4%, well below the national average. Between 2016–2017, 11.3% of girls dropped out due to security fears, compounding long-term educational disadvantage.6 Years of school closures due to military operations and internet shutdowns have disproportionately affected girls’ education. With limited awareness of their rights and little exposure to external support systems, young women are ill-equipped to detect or resist predatory schemes. A study by Save the Children (2022) found that 72% of adolescent girls in rural Kashmir lacked any knowledge about trafficking, sexual consent, or protective legal mechanisms. 7

Another enabling factor is the manipulated local marriage market, shaped by poverty, gender imbalance and prolonged militarization. Families facing economic desperation often perceive marriage as an escape from hardship, a vulnerability traffickers exploit with impunity. Under the claimed administrative control of the Indian government, networks facilitating cross-state “marriages” have operated openly, often without scrutiny. a 2019 report by Inter Press Service details instances where young women from other Indian states were sold into marriages with older men in Kashmir, equating these arrangements to sexual slavery. The report highlights the societal acceptance of such practices and the challenges in prosecuting offenders due to the legal recognition of these marriages.8 Between 2017 6 Noor UL Qamrain, “J&K Worried as School Dropout Rate among Girls Increases - the Sunday Guardian Live,” The Sunday Guardian Live, May 26, 2018, accessed May 1, 2025, https://sundayguardianlive.com/news/jk-worried-school-dropout-rate-among-girls-increases.

10 Rifat Fareed, “‘Breaking the Silence’: Report Documents Torture in Kashmir,” Al Jazeera, May 20, 2019, accessed May 8, and 2022, over 40 such cases were documented in north Kashmir alone, according to findings by Women Against Sexual Slavery (WAS), yet no prosecutions followed.9 The fact that these transactions occurred repeatedly and systematically, without state intervention, strongly suggests tacit approval or willful neglect by security and administrative authorities, raising troubling questions about institutional complicity.

The role of the state in this context is defined more by absence than action. Despite multiple alerts from civil society, the government has failed to enact robust anti-trafficking measures. The 2023 report by Women in Security, Conflict Management and Peace (WISCOMP) highlighted the absence of coordinated law enforcement or victim support systems. FIRs are rarely filed in sexual torture and trafficking cases due to the fear of reprisals at the hands of Indian occupation forces.10 Trafficking is treated as a ‘personal matter’ rather than a systemic crime, reflecting institutional apathy or complicity.

STATISTICS OF MISSING KASHMIRI WOMEN AND GIRLS (2019–2021)

From 2019 to 2021, Jammu and Kashmir recorded a troubling rise in missing women cases, with 9,765 females reported missing, 1,148 girls under 18 and 8,617 adult women, based on official data presented in Parliament. This marks a sharp spike when compared to 3,322 such cases documented between 2016 and 2018, indicating a tripling of disappearances in just three years. Year-wise, 2019 saw 3,093 cases (355 girls, 2,738 women), 2020 recorded 3,051 (350 girls, 2,701 women) and 2021 peaked at 3,621 (443 girls, 3,178 women).11 These numbers were disclosed by the Minister of State for Home, Ajay Mishra, in response to a Rajya Sabha inquiry and are derived from NCRB data.

Government officials attribute this surge primarily to the “excessive use of social media,” which, they argue, facilitates elopements and online luring. However, this official framing overlooks deeper structural issues, particularly in a conflict-ridden region like Kashmir. Analysts highlight how insecurity, weak policing and the erosion of institutional protections contribute more directly to these disappearances. Further, critics suggest that invoking social media is an attempt to depoliticize what may often be cases of trafficking, coercion, or forced relocation. Given the political context and the persistence of militarization, many families suspect foul

play, particularly when young women vanish without a trace or follow-up. While the data itself does not categorically state the nature of each case, human rights groups argue that a significant number may involve trafficking under the guise of marriage, sexual exploitation, or criminal abduction, especially in rural and militarized zones. The disbandment of local women’s commissions and lack of proactive investigation further contribute to the opacity, with no centralized tracking mechanism for follow-up or rescue. The pattern demands a structural, not superficial, response.

DISAPPEARANCE OF WOMEN:ENFORCED, COERCED, OR EXPLOITED?

Disappearances of women in Kashmir have become increasingly frequent, raising alarms among rights groups and local communities. These cases often fall into legal grey zones, with law enforcement framing them as voluntary elopements, despite evidence of coercion. A striking case is that of Hina, an 18-year-old from Ganderbal, who disappeared in 2022 and was later found in Haryana, married to an older man under unclear circumstances. Her case, while resolved, revealed a chain of intermediaries who profited from her relocation. 12 Others have not been so fortunate. Ruksana Ali (20) and Milad Najar (17) were found dead in the Jhelum River, with no autopsies conducted and no investigations launched into possible trafficking or assault13. The refusal to pursue 12 Sajad Hameed, “Wave of Kashmir Disappearances, Mystery Deaths Spook Tribal Community,” Al Jazeera, April 8, 2025,

postmortems in such cases raises concerns of evidence destruction and institutional complicity. Human rights lawyers have noted a pattern of deliberate inaction when victims are women from low-income, conflict-affected households. The influx of migrant laborers post 2019 has complicated the situation. With many local men unemployed, thousands of laborers from Bihar, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh have entered Kashmir’s informal economy. Several missing women cases have been linked to coerced relationships or exploitation by migrant workers. Families allege manipulation under the guise of romance or job offers.

Political reactions have been vocal but inconsistent. Leaders like Shamima Firdous (NC) and Iltija Mufti (PDP) have publicly criticized the state for ignoring these disappearances. AAP members organized protests in Srinagar in late 2023, demanding greater transparency and accountability. Yet, their demands have yielded no policy changes. The absence of a centralized missing persons registry further undermines attempts to track patterns or investigate networks.

STATE COMPLICITY AND IMPUNITY

State complicity is not merely a matter of negligence but a structural issue rooted in militarization and legal immunity. One of the most cited examples is the Kunan-Poshpora incident of 1991, where over 30 women were raped by Indian army personnel. Despite years of litigation and testimonies, no prosecutions have occurred. This case remains emblematic of how the justice system fails women in militarized zones.

More recent cases suggest a pattern of silenceand suppression. Local officials often assist in burying complaints or discouraging families from filing FIRs. Legal barriers institutionalize this impunity. Laws like the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) and the Public Safety Act (PSA) shield occupation forces from prosecution. This legal infrastructure ensures that even when abuses are documented, accountability remains elusive.

The disbanding of the State Commission for Women in 2019 further eroded oversight, leaving victims with no formal grievance redressal mechanism. Despite the applicability of the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956, enforcement in conflict areas like Jammu and Kashmir remains compromised. Legal protections are often suspended under security laws like AFSPA, which shield Indian military personnel from prosecution. Fast-track courts and independent oversight mechanisms are urgently needed to address institutional bias and legal inertia.

CONSEQUENCES FOR WOMEN SURVIVORS

The impact on survivors is both immediate and long-term. Physical abuse includes untreated injuries, reproductive damage and exposure to sexually transmitted diseases. Many women trafficked for marriage or domestic work repor.

being denied medical care. Some return with visible trauma, scars, bruises, or untreated fractures. Psychologically, the damage is profound. A 2022 report by the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS) revealed that 63% of female survivors exhibited symptoms of PTSD. Depression, anxiety and suicidality are widespread, often exacerbated by lack of community support. Survivors also face extreme stigma. Families frequently refuse to accept women back, branding them as ‘dishonoured.’ This social rejection forces many into further cycles of exploitation.

Institutional redress is nearly non-existent. Jammu and Kashmir has only two functional women’s shelters, one in Srinagar and one in Jammu, both underfunded and overcrowded. Legal aid is minimal, particularly for rural women, who face linguistic and bureaucratic

barriers. Rehabilitation programs for trafficking survivors are either defunct or limited to urban centers, failing to reach those most affected. Economic precarity persists even after escape. Without vocational training or economic assistance, many survivors end up in low-paid domestic work, sometimes in exploitative settings. Repeat trafficking is not uncommon. A 2021 report by HAQ: Centre for Child Rights noted cases where survivors rescued from Punjab were later found working under coercive conditions in Srinagar households. 14 14 “Child Rights in India Joint Stakeholder’s Report on the Universal Periodic Review IV of India HAQ: Centre for Child Rights, New Delhi, India (on Behalf of Organisations, Coalitions & Networks)*

PATTERNS, NETWORKS AND STRUCTURAL FACTORS

Trafficking in Kashmir is not random; it is systematized through networks spanning local brokers, organized crime syndicates and in some cases, corrupt officials. Investigations reveal that trafficking routes often overlap with narcotics corridors, especially those linking Punjab and Kashmir. The Narcotics Control Bureau’s 2021 annual report identified shared logistical infrastructure between drug cartels and trafficking operations. Kashmiri girls are trafficked out to states like Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, where bride shortages make them highly ‘marketable.’

Kupwara, Baramulla and Kulgam are trafficking hotspots, owing to porous borders and weak policing. In regions like Baramulla and Pattan, where civil institutions are weak and militarization is high, women are especially vulnerable. Anti-trafficking laws exist, but enforcement is rare, underfunded and selective. Police and state agencies often ignore complaints, citing lack of paperwork or social acceptance of these marriages. Many victims fear retribution and avoid reporting, knowing they are trapped in a system where the army is seen more as an enforcer of control than a protector of rights.

Power asymmetries in Kashmir’s militarized landscape hinder victim reporting. Families fear reprisal not only from traffickers but also from occupation forces, who often treat such complaints with suspicion or hostility. The labeling of critical voices as “anti-national” further silences dissent. Data on trafficking is fragmented. The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) does not maintain a category specific to cross-border bride trafficking or conflict-related disappearances. Local police recordkeeping is largely non-digitized, making it nearly impossible to track serial offenders or identify geographic trends. NGOs estimate actual trafficking figures could be four to six times higher than reported.

ROLE OF INDIAN FORCES IN CROSS-BORDER TRAFFICKING

In IoJK, trafficking of women under the guise of marriage has become a systematic and horrifying reality. Thousands of Kashmiri women have been sold or forced into marriages, often without consent, under coercion or deception. But the abuse does not stop there. Girls from impoverished regions like West Bengal and Assam are also trafficked into Kashmir, lured by false promises of work or a better life, only to be sold as brides. These crimes unfold in a climate of impunity shaped by heavy militarization. The trafficking networks operating in Kashmir are also linked with broader organized crime, including drug trafficking and forced begging. Indian troops stationed in remote areas have been implicated in facilitating these illicit economies, whether through direct involvement or by failing to investigate and prosecute offenders within their ranks.

The Indian army and occupation forces have repeatedly failed to act. Their inaction has raised serious concerns about their role in enabling, or even participating in, these trafficking networks. Survivor testimonies and human rights reports suggest 15 Rifat Fareed, “‘We Have No One’: The Women and Girls Sold as Brides in Kashmir,” Al Jazeera, January 15, 2023, accessed that traffickers operate with the backing of local power structures and, at times, with the silent approval of the military. In some cases, army personnel are direct or indirect beneficiaries of these coerced marriages.

Nazima Begum, from West Bengal, was trafficked to Kashmir in the summer of 2012. She was promised a job in Kolkata, but instead, she was kidnapped and sold into marriage for $250. The man she was forced to marry was 20 years older than her. Arsheeda Jan, a 13-year-old girl from Kolkata, was trafficked to Kashmir between 2003 and 2005. She was told she would work in a shawl factory but was instead sold into marriage to a man 9 years her senior. Despite trying to escape multiple times, she was kept captive and had no contact with her family. Sabeena, trafficked from Kolkata 10 years ago, was promised a better life in Kashmir. Instead, she found herself in a remote area, living in a mud house with her husband,Farooq Ahmad and their children.

Sabeena often reflects on the loneliness of being far from her family and the challenges in her marriage.15 These testimonies shed light on the emotional and physical hardships women face when trafficked for forced marriages in Kashmir. This is not just a social or economic issue. It reflects a deeper crisis of institutional apathy and militarized patriarchy. The trafficking of both Kashmiri women and non-Kashmiri girls into a militarized zone shows how gendered violence is weaponized in the service of state power and silence.

TRAGIC CASES AND STATE NEGLIGENCE

Multiple disappearances illustrate the deadly intersection of trafficking, state neglect and militarized impunity. Fourteen-year-old Milad Najar disappeared in Srinagar and his body was recovered from the Jhelum River without an autopsy. Similarly, Ruksana Ali went missing i January 2021; her body was retrieved 30 days later from the same river, again with no forensic investigation. In contrast, Hina, aged 18, was found safe after three days, underscoring the arbitrary nature of state response. In areas under heavy military surveillance, such disappearances raise serious questions about the role and silence of security agencies.

The recurrence of such cases and the lack of credible investigation, indicates a systemic failure rooted in militarization, unaccountable governance and institutional apathy. Unless India is held accountable under international law, including through the involvement of UN Special Procedures and independent inquiries, trafficking and sexual exploitation will remain a dark undercurrent of the occupation in Jammu & Kashmir.

I. KUNAN-POSHPORA MASS RAPE (1991)

On 23 February 1991, soldiers from the 4 Rajputana Rifles of the Indian Army conducted a night raid on the twin villages of Kunan and Poshpora. 30 women were raped during the cordon-and-search operation. The victims and village leaders filed formal complaints on 27 February, but Indian army officials denied all allegations. The government failed to conduct 16 Human Rights Watch, “RAPE in KASHMIR a Crime of War Asia Watch & Physicians for Human Rights a Division of Human an impartial investigation and no soldiers were prosecuted.16 The Kunan-Poshpora case remains one of the most infamous examples of mass sexual violence perpetrated by Indian forces under the guise of counterinsurgency.

II. SHOPIAN MASS RAPE (1992)

Another brutal case occurred on 10 October 1992, when the 22nd Grenadiers carried out a raid in Chak Saidapora, near Shopian. At least six women were gang-raped, including an 11-year-old girl and a 60-year-old woman. Medical reports documented severe vaginal injuries and a torn hymen in the minor, yet the authorities attempted to discredit the victims’ testimonies. Although a criminal case was registered against the BSF, the government withheld investigation findings and no prosecutions followed.17 This case illustrates the deliberate suppression of evidence and denial of justice for survivors of military sexual violence.

III. HARAN RAPE CASE (1992)

On 20 July 1992, Indian troops raided Haran village near Srinagar. Two women were raped in their homes, one of them pregnant at the time. They reported being beaten, threatened and losing consciousness during the assault. Despite the seriousness of the case, no response received from the Indian government.18 The silence highlighted the systemic impunity enjoyed by perpetrators within the Indian occupation forces.

IV. GURIHAKHAR RETALIATION RAPES (1992)

Retaliatory sexual violence was also reported on 1 October 1992, when BSF personnel attacked the village of Gurihakhar following a militant ambush. Several women were raped, including one who was assaulted at gunpoint while holding her baby. Others were threatened with harm to their children if they resisted. A medical examination confirmed cases of “severe molestation.”19 The social stigma forced some mothers to claim the rapes had happened to them instead of their daughters. Despite multiple inquiries, the government never responded to requests for accountability.

V. 2006 JAMMU & KASHMIR SEX SCANDAL

The 2006 Jammu & Kashmir sex scandal exposed a trafficking and abuse ring involving politicians, police officers and security personnel. A total of 57 individuals were implicated, including ministers, a BSF DIG and a DSP. Minor girls were trafficked and forced into sexual exploitation, some for as little as ₹250. The police recovered video CDs that showed minor girls being sexually abused. The public outcry forced a CBI investigation and the Supreme Court shifted the trial outside Kashmir to ensure fairness.20 Despite evidence, few were convicted, highlighting systemic impunity and deep-rooted complicity within state and security institutions.

VI. HUMAN TRAFFICKING IN KASHMIR (2016– 2021)

Alongside these documented cases of sexual violence by Indian forces, human trafficking has emerged as a growing crisis in IOJK. Between 2016 and 2021, over 13,000 females were reported missing in Jammu and Kashmir and from 2019 to 2021 alone, 1,148 girls under the age of 18 and 8,617 women disappeared. Many of these cases are suspected to involve trafficking networks that exploit the instability caused by armed conflict. Young girls were frequently lured through social media platforms or abducted from economically vulnerable families. Civil society organizations have consistently pointed to state inaction and institutional apathy as enabling factors. Disturbingly, some of the missing were later traced to brothels across northern India.21 Despite the alarming scale of disappearances, official data remains limited and successful prosecutions are rare, reinforcing a climate of impunity.

VII. HANDWARA SEX RACKET & HUMANTRAFFICKING – (2023)

In 2023, three illegal sex rackets were exposed within a single month in Jammu and Kashmir, reflecting the alarming growth of organized trafficking and exploitation. The third case in Kralgund area of Handwara in north Kashmir’s Kupwara district led to the arrest of five individuals, including a house owner, his wife, a sex worker and two clients.22 These cases indicate the operational presence of structured trafficking rings. In several such instances, Indian forces or their informants are allegedly complicit, either by facilitating or by turning a blind eye to these crimes, contributing to the culture of impunity.

SEXUALIZATION OF KASHMIRI WOMEN POST-PAHALGAM

Following the Pahalgam attack, Kashmiri Muslim women became immediate targets of a wave of digital hate, driven by hyper-nationalist discourse. Their bodies were securitized, framed as threats to the imagined purity of the nation and simultaneously as vessels for punishment. This duality reflects Foucault’s notion of biopolitical governance, where bodies are regulated, sexualized, and controlled within the logic of national security. In postcolonial terms, Kashmiri women become the “Other,” inscribed with meanings that justify repression and state violence. 23

The eruption of hate speech across platforms like X reveals a deeper architecture of structural violence. Social media becomes a tool of digital militarism, where the state’s ideological project is outsourced to civilian proxies. The targeting of women through threats of rape and sexual violence is not simply misogynistic, it is political. It constitutes a gendered extension of sovereignty, asserting control over colonized 24 Barbara Trojanowska (reviewer), “Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics,” Australian

Institute of International Affairs, 2015, https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/bananas-beaches-and-bases-mak-ing-feminist-sense-of-international-politics/. bodies to reaffirm majoritarian supremacy. This is performative nationalism, where humiliating the “enemy’s women” becomes a symbolic act of domination.

The use of sexualized threats also reinforces colonial tropes, the Muslim woman as deviant, promiscuous, and in need of control. These are not new narratives but reactivations of older logics of empire, where conquest is both territorial and corporeal. Kashmiri women thus inhabit a precarious position at the intersection of occupation and patriarchy. Their hyper- visibility post-conflict is not a sign of recognition but a mechanism of silencing through fear. As feminist IR scholars such as Cynthia Enloe have pointed out, militarization and gender intersect in ways that reduce women to symbols of national struggle, where their bodies are deployed as ideological battlegrounds. 24

This environment creates a gendered security dilemma. Women are rendered unsafe not only by militarization but also by majoritarian civilians who reproduce the state’s coercive logic. It represents what feminist IR scholars identify as the feminization of insecurity, where gendered bodies become the terrain of power struggles. The structural impunity for hate crimes is part of the broader project of state violence that disciplines dissent and difference. What is also evident is the failure of liberal institutions to safeguard minority citizens.

The silence of law enforcement, the inaction of the judiciary, and the absence of political accountability normalize this gendered hostility. This is a case of state-enabled symbolic violence, where exclusion is not an aberration but a technique of governance. The sexualization of Kashmiri women post-Pahalgam is a continuation of the state’s militarized and patriarchal strategy of control. It turns women’s bodies into ideological battlegrounds, collapsing the distinction between warfronts and home fronts.

INTERNATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORKS AND INDIA’S OBLIGATIONS

UN Security Council Resolution 1325 emphasizes the protection of women in conflict and their role in peacebuilding, especially in addressing sexual violence. However, its implementation in Kashmir remains limited and politically sensitive. The 2018 and 2019 OHCHR reports highlighte dserious abuses against women and called on India to permit independent investigations .India rejected these recommendations, citing concerns over sovereignty. As a result, international efforts to uphold women’s rights under conflict remain stalled in the region.

India, as a signatory to key international human rights and humanitarian law instruments, bears distinct legal responsibilities regarding the protection of women and girls in conflict zones 25 “Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women New York, 18 December 1979,” OHCHR, 27 M. Gandhi, “Common Article 3 of Geneva Conventions, 1949 in the Era of International Criminal Tribunals - [2001] ISILYBIHRL 11,” Worldlii.org, 2001, accessed May 4, 2025, http://www.worldlii.org/int/journals/ISILYBIHRL/2001/11.html. like Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IOJK).

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) mandates state parties to eliminate gender- based violence and ensure legal protections for women, including in conflict-affected areas.25 Likewise, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) obliges India to safeguard the right to life, dignity and freedom from torture or inhumane treatment, rights frequently violated in the context of militarized sexual violence and trafficking in IOJK .26 Furthermore, under the UN Palermo Protocol, India is bound to prevent, investigate and prosecute trafficking in persons, with special emphasis on women and .children as vulnerable groups International humanitarian law also reinforces these obligations. Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions prohibits outrages upon personal dignity, including rape and sexual slavery, during armed conflict. Customary International Humanitarian Law further prohibits sexual violence against civilians and demands humane treatment of all persons not taking active part in hostilities, including detainees.27

Despite these clear legal norms, enforcement in IOJK remains extremely weak. India has ratified most relevant treaties but fails to translate these commitments into effective mechanisms in conflict settings. The absence of a national action plan addressing conflict-related sexual violence and trafficking exposes a critical gap in state compliance with its international obligations and contributes to a culture of impunity within the militarized governance structure of Kashmir. At the international level, India must be pressured to permit the entry ofn UN Special Rapporteurs on Violence Against women and Trafficking.

There is a compelling need for an international inquiry into systemic abuse and trafficking networks operating in IOJK, potentially through the UN Human Rights Council or a special investigative mechanism.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bold. “ILLEGAL SEX TRADE in J&K.” Bold News,April 25, 2023. https://boldnewsonline.com/illegal- sex-trade-in-jk/.

“Child Rights in India Joint Stakeholder’s Report on the Universal Periodic Review IV of India HAQ: Centre for Child Rights, New Delhi,

India (on Behalf of Organisations, Coalitions & Networks).” https://www.haqcrc.org/wp-content/ uploads/2022/04/child-rights-in-india-upr-iv-joint-

stakeholders-report-haq.pdf.

Fareed, Rifat. “‘Breaking the Silence’: ReportDocuments Torture in Kashmir.” Al Jazeera, May 20, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/

news/2019/5/20/breaking-the-silence-report- documents-torture-in-kashmir.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, New York: A Division Of Random

House. INC, 1977. https://monoskop.org/ images/4/43/Foucault_Michel_Discipline_and_

Punish_The_Birth_of_the_Prison_1977_1995.npdf.

FreedomUnited.org. “Trafficked Brides in Kashmir,” January 23, 2023. https://www.

freedomunited.org/news/trafficked-brides-in- kashmir/.

Gandhi, M. “Common Article 3 of Geneva Conventions, 1949 in the Era of International

Criminal Tribunals - [2001] ISILYBIHRL 11.” Worldlii.org, 2001. http://www.worldlii.org/int/

journals/ISILYBIHRL/2001/11.html. [Hameed, Sajad . “Wave of Kashmir

Disappearances, Mystery Deaths Spook Tribal Community.” Al Jazeera, April 8, 2025. https:// www.aljazeera.com/features/2025/4/8/wave-of-

kashmir-disappearances-mystery-deaths-spook- tribal-community.

Hussain, Bilal. “Nearly 10K Women, Girls Go Missing in Kashmir, Sparking Alarm.” Voice of America. Voice of America (VOA News),

August 11, 2023. https://www.voanews.com/a/ nearly-10k-women-girls-go-missing-in-kashmir-sparking-alarm-/7221681.html.

Kashmir Reader. “72% Households in J&K in Rural Areas: Survey,” May 21, 2022.

https://kashmirreader.com/2022/05/22/72- households-in-jk-in-rural-areas-survey/. Knott, Marie Luise, and Margitt Lehbert.

“Intentionally Left Blank.” New England Review

37, no. 3 (2016): 24–37. https://doi.org/10.1353/

ner.2016.0064.

ILO. “Youth Employment, Education and Skills,” 2024. https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/ files/2024-08/India%20Employment%20-%20 web_8%20April.pdf.

Nabi, Safina. “J&K Shuts Women’s Commission, Violence against Women Rises.” Article-14. com. home, December 26, 2020. https://

www.article-14.com/post/j-k-shuts-women-s- commission-violence-against-women-rises. Noor UL Qamrain. “J&K Worried as School

Dropout Rate among Girls Increases - the Sunday Guardian Live.” The Sunday Guardian

Live, May 26, 2018. https://sundayguardianlive.

com/news/jk-worried-school-dropout-rate-among- girls-increases. OHCHR. “Convention on the Elimination of

All Forms of Discrimination against Women New York, 18 December 1979,” 2025. https:// www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/

instruments/convention-elimination-all-forms-discrimination-against-women

PTI. “13.13 Lakh Girls, Women Went Missing between 2019 and 2021: Govt Data.” TheHindu, July 30, 2023. https://www.thehindu. com/news/national/1313-lakh-girls-women-

went-missing-between-2019-and-2021-govt- data/article67138563.ece.

Shah, Umar Manzoor. “For Some in Kashmir Marriage Equates to Sexual Slavery.” Globalissues, October 11, 2019. https://www.globalissues.org/news/2019/10/11/25742.

Shivdas, Meena, and Sarah Coleman. “Without Prejudice CEDAW and the Determination of Women’s Rights in a Legal and CulturalContext,” 2010. https://www.thecommonwealth-

i l i b r a r y. o r g / i n d e x . p h p / c o m s e c / c a t a l o g / download/153/150/1096?inline=1.

Trojanowska (Reviewer), Barbara. Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics. Australian Institute of International Affairs. 2015. https://www.

internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/ bananas-beaches-and-bases-making-feminist- sense-of-international-politics/ United States Department of State. “India -

United States Department of State,” January 6, 2025. https://www.state.gov/reports/2021- trafficking-in-persons-report/india/.

Watch, Human Rights. “RAPE in KASHMIR a Crime of War Asia Watch & Physicians for Human Rights a Division of Human Rights Watch.” Vol

https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/ .1993 ,5 .PDF.reports/INDIA935

Related Reports