A Comparative Study of State Policies under Modi in Kashmir and Netanyahu in Gaza

A Comparative Study of State Policies under Modi in Kashmir and Netanyahu in Gaza

Abstract

The article makes a comparative analysis of the Indian-Occupied Jammu & Kashmir (IOJK) under Narendra Modi and Gaza under Benjamin Netanyahu with regard to utilizing demographic engineering as an instrument of domination. It proposes that regardless of variants in the IOJK (legal-administrative reform) and in Gaza (military-induced displacement), there are similarities in the structural logic through which populations are reconstituted so as to cement sovereignties and undermine indigenous rights.

Authored by:

Basmah Nouman

The analysis is based on the Settler Colonialism Theory, the Securitization Theory, and Realism. The legal reforms of Kashmir with the domicile laws and Israel with the settlement policies are seen as a structural aspect of legal endeavors as collectively postulated through settler colonialism. The idea of securitization shows how the opposition in the two areas is termed as terrorism, which justifies extreme actions such as mass detention to bombardment.

Realism puts an emphasis on the role of selective global responses that are motivated by strategic considerations leading to a support system of such practices. Results indicate that law gives legitimacy and militarization gives compliance, whereas economics restructure local resilience, and cultural suppression rents out collective identity. The cases indicate that the demographic engineering is not an accidental phenomenon but a developed project initiated by the state, which prompts the serious questions concerning the world's accountability and the normalization of such tactics in modern conflicts.

Keywords

Demographic engineering | IOJK | Occupation | Netanayahu | Gaza | Article 370

1. Introduction

The situations of Indian-Occupied Jammu & Kashmir (IOJK) and Gaza reflect the way in which the modern states use demographic engineering and militarized occupation to reconstruct the contested territories. By 27 June, 2025, the UN estimated that there were more than 684,000 individuals displaced again following the collapse of the ceasefire highlighting the massiveness and institutionalization of the movement of people under prolonged hostilities[. Following the abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A in August 2019, 83,742 domicile certificates have been issued to non-state bodies by authorities in IOJK, a legal twist interpreted as facilitating demographic rearrangement as well as a dense security presence and information restrictions[2].

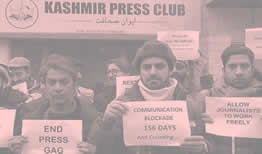

This paper will show that the post-2014 policies of Narendra Modi in IOJK share a common authoritarian logic of territorial consolidation, through law and force, coupled with narrative, and are supported by elastic international reactions to the same. UN human rights reporting has long made note of human rights issues in Kashmir, and international activism in Gaza has brought attention to mass displacement and civilian suffering in general; when placed alongside each other, these accounts trace overlapping forms of boundaries and population regulation. In complement to UN work, Human Rights Watch has documented frequent internet blockages, particularly severe in Jammu & Kashmir[3], as a means to add to the suppression of movement, income, and expression, reinforcing coercive policymaking.

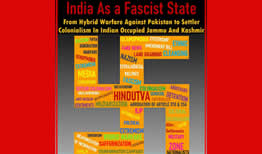

Under the guise of Settler Colonialism Theory, Realism and Securitization Theory, this article aims to discuss the similarities between policies conducted by states in both IOJK and Gaza, especially with regard to demographic engineering and militarized occupation, as well as looking at how the subdued global reaction to Israeli activities has given India the confidence to follow suit. It proposes the hypothesis that since 2014, systematic settlement and security-based domination of IOJK by India belongs to a pattern similar to those used by the Netanyahu government in Gaza, which thrives on the permissive environment established by interest-based partisan advocacy in the international arena.

3. Theoretical Foundations

3.1 Key Concept

The relationship between demographics and war cannot be denied. There is an option to either help protect or become a serious threat to the population of any political unit. Thus, the increase or decline in population has always been a major security issue for any political unit.

There is a plethora of literature which covers demographic engineering in general such as the works by Theodore P. Wright, Milica Zarkovic Bookman, John McGarry and Myron Weiner. According to Theodore P. Wright Jr., demographic engineering may be viewed as the fact that in case the governing elite of an ethnically different population group does not constitute a majority of the population, then this group is likely to notice this oversight and initiate the pursuit of a number as a tool of preventing their own extinction.[4

] John McGarry writes about demographic engineering as a state attendant purposeful means of conflict management. He postulates that the governments possess several options that they can use to transform the composition of people in an area of conflict[5]. They can either encourage or reward loyalty groups to relocate to areas where minorities are the majority, and in most cases, disengaged communities are displaced, moved to other areas, or even forced to leave the country completely.

3.2 Core Theories

Settler Colonialism Theory:

In the wake of Patrick Wolfe, who has written that settler colonialism is a structure, not an event[6], the lens will be used to examine projects that point toward regime control of land via legal, demographic and coercive measures. When applied to India, the domicile policy of IOJK, operationalized in 2019 due to the expansion of the residency status, land rights, and the right to work in the sphere of the state public sector for non-locals, serves as an instrument of law that can be used to resettle the population and neutralize the indigenous political base. In the Israeli instance, the settlement project (legalization/expansion of outposts, land seizures, and infrastructure to institutionalize settler presence) also incorporates a long-term demographic bias. In both cases, law and administration do the slow, structural work, and the security forces occupy the territory created through the law.

Realism

According to realism, conflicts are met by calculating the power, alliance, and material interests of the states and blocs instead of being met with moral consistency. The attitude of the U.S.[7] and other major EU states[8] toward defense, tech, and market partners Israel and India[9] falls along this logic: loud rhetorical interest, little coercive investment. The presence of arms cooperation, supply-chain relationships and regional balancing may be used to underpin why selective censure is not enforced in Gaza, and the lack of enforcement against IOJK is muted and non-binding. These patterns under realist reading decrease external constraint and increase the expected payoff of demographic and security policies of both governments.

Securitization Theory

According to Barry Buzan and co-authors, the political players may convert mundane matters into threats of existence in terms of providing security[10], as a result of which launching extraordinary actions is justified. In IOJK, the government has been habitually labeling dissent, whether street protests, civil

society action, or even information flows terrorism or separatism[to justify months-long internet shutdowns, mass arrests, and expanded police authority. In Gaza, Israeli leaders frame Palestinian resistance as a blanket terrorist threat[1providing rationalizations for blockade logics, loose rules of engagement, and evacuation/displacement on a mass scale. The securitizing move in the two contexts transforms the argument of rights and representation into a discussion about emergency management, which makes demographic engineering and militarization of governance seem not only possible but essential.

These lenses are combined in the comparative analysis below: Settler colonialism defines the structural objective (long-term domination of population demographics), securitization covers the day-to-day justification of exceptional means to execute that objective, and realism explains the accommodating international environment in which to pursue it.

4. Comparative Analysis

The similarities between IOJK and Gaza are the most visible when the policies of demographic engineering are considered in the perspectives of settler colonialism, securitization, and realism. Even though the instrumentality varies, namely constitutional reforms and administrative transformation in Kashmir and military occupation and blockade in Gaza, the logic of the structure of the control bears similarity towards transforming populations and reaffirming sovereignty.

In Kashmir, the Indian state has considered legal and administrative methods of attaining demographic change. With the abrogation of Article 370 and the implementation of domicile laws, there emerged a methodological route through which non-locals were permitted to obtain residency and land within a formal legal context and designed into the landscape of constitutional law. The Israeli strategy, which is more pronounced in the West Bank, works along the same lines. Long-term population rearrangement is supported by laws that govern settlement, which legitimate land acquisition in the name of legality (lawful matrimony), and zoning rules. In either scenario, law is a settler colonizing tool, providing the illusion of routine administration that fulfills a more fundamental role of demographic restructuring.

These juridical constructs cannot be dissociated from the role of occupation forces that become the guarantors of demographic change. In IOJK, the glut of security forces and regular shutdown of communications have been justified as counterterrorism interventions, turning civilian areas into securitized triangles. In Gaza, the situation is more disruptive: bombardments, mass eviction orders, the declaration of huge territories as military exclusion zones turn whole communities into displaced people. In this case, the securitization theory is especially informative: both states frame the local resistance in terms of terrorism, thus allowing exceptional measures that are otherwise outside of the legal or moral jurisdiction. They may be in the muffled, long-term permanence of troop deployment in Kashmir or the brutality of Israeli military actions on Palestine in Gaza, but truth is always underpinned with force to make legal and political change into an everyday tangible reality.

There is the economic aspect of control in terms of occupation as well. In Kashmir, the liberalization of land markets to external investors and curtailments of local trade by means of curfews and internet blocks instill dependency on the central administration. Things have not been the same in Gaza where the siege has wiped off infrastructure and reduced the enclave into near complete reliance on international charity. However, regardless of such contrastive modalities, one based on integration and the other on deprivation, the effect is incongruently close: the destruction of native economic vigor and the strengthening of a foreign center of power.

Lastly, demographic engineering is solidified at the symbolic level by psychological and cultural suppression. The limitation of the freedom of media, religion, and independence of education in Kashmir not only disclaims the Kashmiris but also legitimizes state-endorsed versions. In Gaza, multiple bombardments of universities, cultural centers and civil society organizations undermine Palestine solidarity and wipe away areas of communal memory. This level highlights the point made by Patrick Wolfe that settler colonialism is not only aimed at getting rid of the native physically, but it is aimed at getting rid of them symbolically as well, so that the alternative claim to the property would not only be occluded but deprived of any credibility.

Collectively, these trends can lead us to the conclusion that, despite the dissimilarities between the contexts and approaches, India and Israel follow the same structural logic: the law authorizes, militarization enforces, economics reimages, and culture undermines. The conceptualization of demographic engineering in IOJK and Gaza through the concrete theoretical lenses used in this paper means that it is not an afterthought to conflict as conventionally understood, but rather an end-to-end project of the state powered by the securitized discourse and supported by a softer international order.

5. Conclusion

The comparative analysis of IOJK under Narendra Modi and Gaza under Benjamin Netanyahu has shown that the element of demographic engineering acts as intentional state policy and not as an unintended consequence of the conflict. In both cases, there are four layers to these policy interactions that remake the populations and cement foreign rule that include legal institutions, militarization, economic reorganization, and cultural repression. Even though India moves to focus more on constitutional reform and administrative integration and Israel on military coercion and blockade, the logic of structure remains convergent, as they use state arms to undermine native property rights to territory and routinize exceptional rule.

The impacts are morally dramatic. Both in IOJK and Gaza, demographic engineering constitutes a very grave concern in regard to the principles of international humanitarian law, in particular, the incidence of breaching the Fourth Geneva Convention regarding the prohibition of population transfer. More importantly, the very fact that such practices are being institutionalized proves the very credibility of the international order in general, amounting to the fact that state sovereignty and strategic interests are much more important than the universality of rights.

Unless stopped, the combination of these strategies threatens to institutionalize an insidious de facto: the ability of states to redefine demographic and political realities in the name of law and security, at the encouragement of other states, and the acquiescence of the international community. There is more than verbal denunciation that is needed in this respect. It requires long-term mechanisms of international accountability, increased civil society action, and reprioritization of human rights in world governance. Otherwise, in the absence of action, the cases of IOJK and Gaza might not be isolated instances but precedents for future conflicts when the practice of demographic manipulation as a form of statecraft would become normalized.

Bibliography

Bhatt, Himanshu. 2024. “India: Authorities must end repression of dissent in Jammu and Kashmir.” Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/09/india-authorities-must-end-repression-of-dissent-in-jammu-and-kashmir/.

Bookman, Milica Z. 2013. The Demographic Struggle for Power: The Political Economy of Demographic Engineering in the Modern World. N.p.: Taylor & Francis Group.

Buzan, Barry, Ole Wæver, and Jaap d. Wilde. 1998. Security: a new framework for analysis. N.p.: Lynne Rienner Pub.

Constantin, Sergiu, and Andrea Carlà. 2025. “The Vicious Circle of Securitization Processes in the Former Indian State of Jammu and Kashmir.” Journal of Global Security Studies 10 (01). ogae034.

“Database on fatalities and house demolitions.” n.d. Database on fatalities and house demolitions. Accessed August 16, 2025. https://statistics.btselem.org/en/demolitions/pretext-unlawful-construction?structureSensor=%5B%22residential%22%2C%22non-residential%22%5D&tab=overview&stateSensor=%22west-bank%22&demoScopeSensor=%22false%22.

Fernández, Belén. 2022. “Israel: normalising terror, one dawn at a time.” Al Jazeera, August 12, 2022. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2022/8/12/israel-normalising-terror-one-dawn-at-a-time.

“Former EU ambassadors warn: Europe's silence on Gaza is complicity.” 2025. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2025/7/31/former-eu-ambassadors-warn-europes-silence-on-gaza-is-complicity.

“Gaza crossings: movement of people and goods | United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs - Occupied Palestinian Territory.” 2025. OCHA oPt. https://www.ochaopt.org/data/crossings.

“Gaza: Operation Protective Edge.” 2025. Amnesty International UK. https://www.amnesty.org.uk/gaza-operation-protective-edge.

Hafeez, Mehwish. 2024. “Demographic Engineering: A Case Study of Indian Occupied Jammu and Kashmir,” Online Article. In Islamabad Papers 2024 (no. 52). N.p.: ISSI. https://issi.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IP_No_52_2024.pdf.

“Humanitarian Situation Update #307 | Gaza Strip [EN/HE].” 2025. UN OCHA. https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/occupied-palestinian-territory/humanitarian-situation-update-307-gaza-strip.

“India: Repression Persists in Jammu and Kashmir.” 2024. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/07/31/india-repression-persists-jammu-and-kashmir.

Kazmee, Saira. 2021. “SYSTEMATIC CHANGES IN DEMOGRAPHIC COMPOSITION OF JAMMU AND KASHMIR BY INDIA AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR THE RESOLUTION OF KASHMIR CONFLICT.” Ilkogretim Online, 2021 20 (05): 2568-2577. doi: 10.17051/ilkonline.2021.05.278.

Khan, Hasnain. 2024. “The Role of International Organizations in Addressing the Jammu and Kashmir Conflict.” Kashmir Institute of International Relations. https://www.kiir.org.pk/Research-Paper/the-role-of-international-organizations-in-addressing-the-jammu-and-kashmir-conflict-8397.

Khawaja, Shazia, and Mehr u. Nisa. 2023. “Human Rights Report June-August 2023,” Report. Kashmir Institute of International Relations. https://www.kiir.org.pk/reports/humman-rights-report-7069.

Khoury, Elias. 2024. “Why has America risked it all in Gaza?” Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2024/8/4/why-has-america-risked-it-all-in-gaza.

Majid, Zulfikar. 2025. “Over 83000 Outsiders Granted Domicile Certificates in J&K Post-Article 370.” Deccan Herald. https://www.deccanherald.com/india/jammu-and-kashmir/amid-demographic-concerns-jammu-and-kashmir-govt-says-83000-outsiders-granted-domicile-certificates-3485715.

McGarry, John. 2010. “'Demographic engineering': the state-directed movement of ethnic groups as a technique of conflict regulation.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 21, no. 04 (December): 613-638. 10.1080/014198798329793.

““No Internet Means No Work, No Pay, No Food”: Internet Shutdowns Deny Access to Basic Rights in “Digital India” | HRW.” 2023. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/06/14/no-internet-means-no-work-no-pay-no-food/internet-shutdowns-deny-access-basic.

“Occupied Palestinian Territory.” 2025. OCHA. https://www.unocha.org/occupied-palestinian-territory.

Raashed, Maryam. 2020. “Decoding Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Order 2020.” Center for Strategic and Contemporary Research. https://cscr.pk/explore/themes/politics-governance/decoding-jammu-and-kashmir-reorganisation-order-2020/.

Singh, Vijaita. 2020. “The Hindu Explains | Who can buy or sell land in J&K, and what are the other rules governing it?” The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/the-hindu-explains-who-can-buy-or-sell-land-in-jk-and-what-are-the-other-rules-governing-it/article61942423.ece.

Sirayon, Hawa. 2024. “CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE DYNAMICS OF ISRAEL - PALESTINIAN CONFLICT BASED ON THEORIES OF INTERNATIONAL SECURITY.” Journal of Diplomacy, Peace and Conflict Studies 01 (01): 5-9. https://quantresearchpublishing.com/index.php/jdpcs/index.

Uddin, Imad. 2019. “Indian military deployment in IoK largest troops concentration in any occupied territory: Masood.” Business Recorder. https://www.brecorder.com/news/515428.

“UNRWA Situation Report #177 on the Humanitarian Crisis in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem.” 2025. UNRWA. https://www.unrwa.org/resources/reports/unrwa-situation-report-177-situation-gaza-strip-and-west-bank-including-east-jerusalem.

Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. “Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native.” Journal of Genocide Research 08 (04): 387-409. 10.1080/14623520601056240.

[1](“UNRWA Situation Report #177 on the Humanitarian

Crisis in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem” 2025)

[2] (Bhatt 2024)

[3](“India: Repression Persists in Jammu and Kashmir”

2024)

[4] (Bookman 2013, 32-33)

[5] (McGarry 2010, 615)

[6] (Wolfe 2006)

[7] (Khoury 2024)

[8] (“Former EU ambassadors warn: Europe's silence on

Gaza is complicity” 2025)

[9] (Khan 2024)

[10] (Buzan, Wæver, and Wilde 1998, 141-142)

[11] (Constantin and Carlà 2025, 6-13)

[12] (Sirayon 2024, 6-7)

Related Research Papers