Trapped Between Fear and Resistance: Youth Identity Under Occupation in IIOJK

Trapped Between Fear and Resistance: Youth Identity Under Occupation in IIOJK

Abstract

This paper discusses the psychological impact of military occupation on the identity of young people in Indian illegally occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK) using the theory of Postcolonialism. Based on secondary data and the qualitative approach of content analysis, it notes how years of exposure to violence, curfews, surveillance, and cultural repression create extremely traumatic, depressed, and identity-confused Kashmiri youths.

The study also concludes that resilience is developed through social networks, cultural practices, and artistic forms of protest that are demonstrated in poetry, rap, and art. The study highlights the youth as the victims of oppression and creators of resistance and reclamations of identities.

Keywords: Postcolonial Theory, Youth Identity, Psychological Effects, Kashmir Conflict

Researcher: Huzaifa Imtiaz

Introduction

Indian Illegally Occupied Jammu Kashmir (IIOJK) is a

historically war torn and militarized state that has suffered decades of

political humiliation and military occupation, to become one of the most

militarized regions in the world. Surveillance, limited movement, frequent

curfew, and high military presence have characterized Kashmir since the late

twentieth century. For young people growing up in this environment, such

conditions are not occasional disruptions but an everyday reality. Life full of

fear, uncertainty and political tension must have an immeasurable effect not

only on their psychological state but also on their identity development.

The study is about an aspect that is a concern and

yet seldom discussed of the Kashmir conflict: the impact of the occupation on

the lives and perception of young Kashmiris. Though significant amount of

research has been conducted witnessing political, economic and human rights

effects of the occupation, surprisingly little research has been recorded on

the effects the Indian occupation has had on mental health as well as its

effect on identities. The youth of IIOJK have had to deal with an ongoing

conflict between the historical narratives imposed by the occupier, and their

own cultural, religious, and national identities that, in most cases lead them

to resist and to develop a lot of trauma.

It is an important subject in conflict and

postcolonial studies since it mediates the gap between structural oppression

and the psychology of a person experiencing it. The way occupation influence

youth identity is not an academic matter only, but also part of establishing

interventional processes, which would benefit those living in conflict in terms

of mental health and self-determination. It can also be applied to inform our

more general discourse about how the generational identity could be influenced

by historical tensions that might perpetuate a cycle of opposition, exclusion,

and turmoil.

The proposed study will be inclined towards

researching the psychological impacts of decades of military occupation of

IIOJK on its young people by considering the Postcolonial Theory framework. The

focus of the study is on mental well-being, struggles with identity, and forms

of resilience or resistance. This research uses secondary sources like

literature, reports, and media to explore how fear and control shape the inner

lives of young Kashmiris, giving a perspective on the conflict that is usually

discussed in political terms rather than personal ones.

Research Questions and Objectives

Research

Questions:

1.

How does

military occupation affect the self-perception and identity of Kashmiri youth?

2.

What

psychological impacts do young people in IIOJK face under prolonged conflict?

3.

How do Kashmiri

youth express resistance or redefine identity under occupation?

Research

Objectives:

·

To explore

psychological and identity changes in youth under occupation.

·

To identify

forms of expression and coping mechanisms in response to trauma.

·

To contribute

insights to academic discourse on youth in militarized zones.

Literature Review

Global Context: Psychological Impacts of Occupation and Conflict

The studies on countries that have been under

long-term occupation, like Palestine, Bosnia, and Sri Lanka, always show

increased psychological trauma in the young generation. For instance, studies

from the Kashmir Valley report a high prevalence of post-traumatic stress

disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression, linked closely to cumulative exposure

to traumatic events, militarization, and insecurity.[1] These

results align with larger patterns of conflict: previous incidences of trauma

may last over decades, which has a strong impact on psyche and psychosocial

status.

Beyond immediate psychological effects, conflict

environments also shape the long-term trajectories of youth. Ongoing

instability and experiences of perceived injustice intensify psychological

distress and disrupt identity formation, as demonstrated in comparative

research on various conflict-affected populations.[2]

While global research highlights trauma’s psychological burden, less is

understood about how these disruptions affect identity formation in youth

confined to militarized or occupied regions.

Youth Identity Studies: Identity Formation in Adolescence

Adolescence is widely acknowledged as a critical

period for identity formation. Erikson’s psychosocial theory identifies the

stage of identity versus role confusion during adolescence, where individuals

grapple with the question, “Who am I?” Successful resolution brings a coherent

sense of self, while failure leads to confusion and instability.[3]

Identity development is seen as both individual and social, a blend of personal

choices and societal expectations.[4]

Longitudinal studies show relative stability in

identity commitments during adolescence, while deeper exploration increases

with age.[5] In

conflict and diverse settings, adolescents face added complexity: they must

navigate identity formation amid disruption, threat, and altered social

paradigms.[6]

These dynamics underscore how conflict can disrupt normal developmental

pathways and complicate youth’s sense of agency and belonging.

Existing Kashmir Research: Political and Human Rights Dimensions

Studies on Kashmir often focus on the political

conflict and human rights violations such as detentions, disappearances,

restricted mobility, and abuse, including the specific targeting of women and

children.[7]

Reports note that ongoing exposure to violence and institutional oppression

induces widespread mental distress across populations, with 47% trauma

prevalence, 41% depression, 26% anxiety, and 19% PTSD among adults.[8]

These works detail the structural impacts of occupation but rarely center on how these external pressures shape youth identity internally. Instead, they emphasize systemic issues and adult-level trauma, leaving a gap in exploring youth identity trajectories in the face of sustained conflict.

Literature Gap: Youth Identity Formation under Occupation in IIOJK

While there is substantial literature on

conflict-driven trauma and degrading human rights in Kashmir, there's a clear

absence of focused analysis on how occupation affects identity formation among

Kashmiri youth. Most studies address political, security, or societal-level

concerns—but few investigate the psychological and developmental dimensions of

identity under occupation.

By centering Postcolonial Theory, the proposed study

aims to explore how colonial-style power structures disrupt youth's internal

sense of self. Through analyzing secondary narratives such as literature,

media, personal accounts, and reports, this research will examine how youth

reconcile imposed identity frameworks with their own cultural, communal, and

self-defined identities. It will explore the psychological struggle between

internal coherence and external oppression, a dimension largely unexamined in

existing scholarship.

Theoretical Framework

This study adopts Postcolonial Theory as the lens to

analyze how prolonged military occupation in IIOJK shapes youth identity.

Central to this theory are themes of power, cultural suppression, identity

formation, and resistance. It frames occupation not as a temporary disruption

but as a pervasive structure that constructs subjectivities and governs modes

of self-expression.

Two leading thinkers in postcolonial theory, Frantz

Fanon and Edward Said, offer crucial insights. Fanon’s work, particularly Black

Skin, White Masks, explores how colonial domination fractures the self, as

colonized individuals internalize inferiority and adopt "white masks"

to survive in a hegemonic culture. His later text, The Wretched of the Earth,

argues that true decolonization emerges through struggle, where literature,

culture, and revolutionary praxis shape a new national identity rather than

nostalgic returns to a romanticized past.[9]

Edward Said’s Orientalism critiques how Western

power constructs the "Orient" as inferior and static, a process that

legitimizes domination.[10]

Said shows how these hegemonic narratives distort colonized identities, leading

to internalized alienation and fractured self-concepts, a dynamic with deep

psychological consequences.[11]

Applying these concepts to IIOJK:

·

Occupation

functions like colonial rule, imposing identity through surveillance, control,

and cultural narratives that frame Kashmiri youth as 'other'—dangerous,

backward, or suspect. This mirrors Fanon’s "white mask" phenomenon

and Said’s processes of "othering."

·

Youth identity

becomes a site of contestation: Kashmiri youth may mask or suppress their

authentic selves to navigate authority, while internal identity struggles

parallel Fanon’s descriptions of alienation and inferiority.

·

Resistance

expressions such as poetry, social media storytelling, cultural reaffirmation, constitute

decolonial identity work, reminiscent of Fanon’s vision of combat literature

and national culture forged through struggle.

By centering Postcolonial Theory, this research

explores how occupation molds psychological experiences and identity formation

among youth, not merely through trauma or repression but through resistance,

cultural assertion, and the contested terrain of self-definition.

Methodology

This study employs a qualitative research design,

with a focus on content analysis of secondary sources. Since direct fieldwork

such as interviews or surveys is not feasible in the current context of IIOJK,

the research relies on existing scholarly and documentary evidence to capture

the lived experiences of Kashmiri youth.

Data Sources: This study relies on a broad range of secondary

sources, including peer-reviewed articles, books, human rights reports,

psychological research, news media, autobiographical accounts, documentaries,

and social media narratives. Together, these materials offer important

perspectives on the psychological experiences, identity challenges, and

resistance practices of Kashmiri youth living under prolonged occupation. In

particular, social media has emerged as a contemporary platform where young

people express trauma, resilience, and cultural identity through creative forms

such as poetry, art, and digital activism.

Data Analysis:

The study employs thematic content analysis to identify patterns, recurring

issues, and underlying meanings within selected texts. Emerging themes will be

coded into key categories such as psychological distress (e.g., trauma,

anxiety, depression), identity struggles (e.g., cultural suppression,

alienation, resistance identity), and coping or resistance strategies (e.g.,

activism, community support, religious faith). Through this analytical process,

the study seeks to demonstrate how occupation not only impacts mental health

but also reshapes processes of identity formation among Kashmiri youth.

Limitations: This research is limited by its reliance on

secondary data, which cannot fully capture the personal nuances of lived

experiences. The absence of direct interviews or surveys restricts access to

the richness of firsthand perspectives. Nonetheless, the triangulation of

multiple sources enhances reliability and provides a comprehensive

understanding of the topic.

Analysis and Findings

Psychological Distress

The Kashmiri youth in IIOJK are under extreme

psychological distress that exists due to high levels of militarization and

structural oppression. A recent study revealed that 100 percent of young adults

recalled experiencing traumatic events, such as anxiety caused by curfews, fear

of crackdowns and witnessing violence.[12]

Mental health data highlights high rates of psychiatric conditions: depression

prevalence at 55.7%, especially among those aged 15–25.[13]

Another survey indicated 45% of adults with probable psychological distress,

with 41% facing depression, 26% anxiety, and 19% PTSD.[14]

These statistics reveal traumas that are

simultaneously personal and collective. Repeated lockdowns, pervasive

surveillance, disrupted education, and the erosion of personal security, often

manifested in panic attacks and the breakdown of daily routines, underscore the

profound emotional instability characterizing the region. One girl, Aasiyeh,

reports how delays by military convoys caused her the greatest anxiety,

interfering with her exam schedule and daily life rhythm.[15]

From a postcolonial perspective, such distress illuminates how occupation

structures are not merely political, they are intimately psychological,

instilling fear and undermining youth’s agency.

Identity Struggles

The long term occupation has affected the identity

of the youths through culture erosion, internalized alienation, and conflicts

between tradition and modernity. A substantial number of young Kashmiris are at

crossroads between their rich culture and the cultural homogenization that is

imposed on them by state propaganda and digital westernization.

One anonymous youth wrote: “I feel a deep sense of

disheartenment… they are desperate to be anything but Kashmiri… the first stage

of cultural death is the loss of language.”[16] Similarly,

tensions between tradition and digital modernity sharpen identity dilemmas: “They

are Kashmiri in heart but global in their habits… This dichotomy fosters… a

subtle disconnection.”[17] These

ambiguous identities reflect what Postcolonial Theory identifies as “othering” where

young people struggle to reconcile imposed identity structures with their

cultural roots, leading to identity confusion and internalized pressure to

conform to externally defined norms.

Coping Mechanisms and Resilience

In the context of Kashmir’s protracted conflict,

formal mental health services remain scarce and stigmatized. Many young people

self-medicate with prescription antidepressants, sedatives, and illicit

substances to address anxiety and insomnia, as mental health professionals are

scarcely accessible and culturally taboo remains strong.[18]

Traditional and community-based coping mechanisms

persist despite the lack of institutional care. Six focus group discussions in

Kashmir revealed that communal spaces, shared chores, cultural practices,

shrines, and faith healers serve as important emotional support systems and

resilience resources.[19]

Social rituals and religious engagement mitigate the experience of distress by

offering social connectedness and culturally rooted solace, echoing global

findings on the mental health benefits of religiosity.

Economic adversity further compounds psychological

strain; studies show that unemployed youth in Kashmir experience significantly

higher levels of anxiety, depression, and overall psychological distress

compared to their employed counterparts.[20]

Despite these stressors, strong familial bonds and peer networks bolster

emotional stability. A quantitative study of young adults exposed to conflict

highlighted that perceived social support from family, friends, and community was

positively associated with resilience, particularly among those optimistic

about Kashmir’s future resolution.

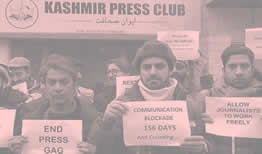

Expressions of Resistance Through Art, Poetry & Social Media

Kashmiri youth have turned to art as both a means of

healing and a form of political resistance, using creative expression as a tool

of dissent under occupation. One of the most influential voices in this

movement is MC Kash, whose 2010 rap I Protest (Remembrance) became an anthem

during the Kashmir unrest. The song’s powerful message captured the spirit of

collective defiance and strongly resonated with young Kashmiris searching for a

voice against state oppression.[21]

More than just rap, graffiti and street art have

also served as silent yet potent tools of protest. During the 2008–10

uprisings, walls across Srinagar and other towns were adorned with slogans like

“We want freedom” and “I Protest,” embodying a vivid, grassroots resistance

even as authorities attempted to erase them.[22]

As one café owner in Srinagar observed, “We always had art in Kashmir, but

recently young people started using it to protest,” noting how poetry, music,

cartoons, and murals have become essential platforms amid censorship and

surveillance.[23]

This form of creative resistance resonates with

Postcolonial Theory, particularly Fanon’s concept of combat literature, in

which cultural production serves simultaneously as a psychological outlet and a

mode of political struggle. Kashmiri youth resist imposed narratives by

employing art to assert their identity, articulate experiences of trauma, and

challenge institutional control. Their creative expressions serve not only as

acts of resilience and collective memory but also as a means of affirming

culture as a foundation for resistance and self-determination under occupation.

Linking to Postcolonial Theory

The findings with the prism of the Postcolonial Theory

show that the process of occupation dominates Kashmiri youth both politically

and existentially. The climate of fear reflects Fanon’s notion of internalized

oppression, while the identity confusion mirrors Said’s “orientalization,”

where imposed identities disrupt self-understanding. At the same time, cultural

rituals, poetry, and music act as decolonial practices that affirm identity,

provide psychological relief, and help Kashmiri youth reclaim their narratives.

Table 1 Summary of

Findings

Conclusion

The occupation youth identity analysis in IIOJK

reveals that the long-term nature of militarization, which goes beyond politics

and economics, has a profound impact on the self-image of the younger generation,

their society, and the future. Kashmiri youth face significant psychological

distress, including trauma, anxiety, and depression, which disrupt normal

identity formation. Simultaneously, they feel alienated culturally between

state-imposed narratives, the global influences, and their cultural traditions.

Yet, the study also highlights resilience and

agency. Regardless of the repression, young people turn to cultural practices,

community relationships, and imaginative expressions in form of poetry, music

and digital activism. These outlets provide psychological relief while also

serving as platforms for asserting identity and reclaiming narrative. Viewed

through the lens of Postcolonial Theory, such acts reflect the struggle of the

colonized to resist imposed otherness and reconstruct identity on their own

terms.

The findings suggest that resolving the conflict

requires more than political negotiations, extending to mental health support

and youth empowerment. Addressing breaches of cultural identity, along with the

resulting despondency and self-distrust, is essential to break cycles of

alienation and depression. Ultimately, the experiences of Kashmiri youth reveal

both the destructive psychological impact of occupation and the enduring resilience

of resistance rooted in culture and identity.

References

1. Housen, T., A. Lenglet, C. Ariti, S. Shah, H. Shah,

S. Ara, K. Viney, S. Janes, and G. Pintaldi. “Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression

and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the Kashmir Valley.” BMJ Global Health 2,

no. 4 (2017): e000419. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000419

2. Shoib, S., R. Mushtaq, S. Jeelani, J. Ahmad, M. M.

Dar, and T. Shah. “Recent Trends in the Sociodemographic, Clinical Profile and

Psychiatric Comorbidity Associated with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Study

from Kashmir, India.” Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research (JCDR) 8, no.

4 (2014): WC01–WC06. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/7885.4282

3. Cherry, Kendra. “Identity vs. Role Confusion in

Psychosocial Development.” Verywell Mind. Updated December 4, 2023. https://www.verywellmind.com/identity-versus-confusion-2795735

4. Arduini-Van Hoose, Nicole. “Identity Development

Theory.” In Adolescent Psychology. Hudson Valley Community College. Lumen

Learning. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/adolescent/chapter/identity-development-theory/

5. Klimstra, T. A., W. W. Hale III, Q. A. Raaijmakers,

S. J. Branje, and W. H. Meeus. “Identity Formation in Adolescence: Change or

Stability?” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 39, no. 2 (2010): 150–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9401-4

6. McKeown, S., D. Cavdar, and L. K. Taylor. “Youth

Identity, Peace and Conflict: Insights from Conflict and Diverse Settings.” In

Children and Peace, edited by N. Balvin and D. J. Christie. Peace Psychology

Book Series. Cham: Springer, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22176-8_12

7. Malik, Laraib. “Psychological Impacts of Conflict:

Case Study of Kashmiri Women.” KIIR. Psychological Impacts of Conflict: Case

Study of Kashmiri Women. Accessed August 16, 2025. https://www.kiir.org.pk/Research-Paper/psychological-impacts-of-conflict-case-study-of-kashmiri-women-4472

8. Arduini-Van Hoose, Lucia. “Social Theory: Frantz

Fanon.” SEPAD. July 5, 2022. https://www.sepad.org.uk/announcement/social-theory-frantz-fanon

9. Fincken, Ella. “The Legacy of Otherness in the

Postcolonial World.” Arcadia. November 27, 2022. https://www.byarcadia.org/post/the-legacy-of-otherness-in-the-postcolonial-world

10. AlAli, Talha. “Edward Said’s Perspective on Culture,

Identity, and Mental Health.” decolonised minds. January 17, 2025. https://decolonisedminds.ie/edward-saids-perspective-on-culture-identity-and-mental-health

11. Dar, A. A., and S. Deb. “Prevalence of Trauma Among

Young Adults Exposed to Stressful Events of Armed Conflicts in South Asia:

Experiences from Kashmir.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice,

and Policy 14, no. 4 (2022): 633–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001045

12. Amin, S., and A. W. Khan. “Life in Conflict:

Characteristics of Depression in Kashmir.” International Journal of Health

Sciences 3, no. 2 (2009): 213–23. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3068807/

13. Oza, Ekta. “Childhoods under Military Occupation:

Everyday Experiences and ‘Insistence on Existence’ as Resistance in Kashmir.”

Settler Colonial Studies 15, no. 2 (2024): 361–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2024.2426111

14. KashmiriCulture. “Imitation Over Identity: Our

Cultural Decline.” r/Kashmiri, June 5, 2025. https://www.reddit.com/r/Kashmiri/comments/1i5q994/imitation_over_identity_our_cultural_decline/

15. Pandita, Sanjay. “The Kashmiri Youth between Legacy

and Login.” Rising Kashmir, April 14, 2025. https://risingkashmir.com/the-kashmiri-youth-between-legacy-and-login/

16. Bukhari, Arsalan. “Young People Self-Medicate as

Kashmir’s Mental Health System Fails Them.” Health Policy Watch, June 3, 2025. https://healthpolicy-watch.news/young-people-self-medicate-as-kashmirs-mental-health-system-fails-them/

17. Bashir, Aabid, Erum Batool, Tanya Bhatia, Sheikh

Shoib, Nisar A. Mir, Uzma Bashir, Ruchita Singh, Margaret McDonald, Mary E.

Hawk, and Sameer Deshpande. “Community Practices as Coping Mechanisms for

Mental Health in Kashmir.” Social Work in Mental Health 21, no. 4 (2023):

406–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2022.2159779

18. Bhat, Mushtaq Ahmad, and Jyoti Joshi. “Impact of

Unemployment on the Mental Health of Youth in the Kashmir Valley.” Journal of

Psychology & Psychotherapy 10 (2020): 373. https://doi.org/10.35248/2161-0487.20.10.373

19. Mathew, Ruth Susan. “The Rap of Kashmir: Hidden

Transcripts of Oppositional Resistance.” IIS University Journal of Arts 10, no.

2 (2021): 107–20. https://iisjoa.org/sites/default/files/iisjoa/Dec%202021/11.pdf

20. Shah, Fahad. “Resistance and Express: Art in the

Valley of Kashmir.” Cerebration. Accessed August 23, 2025. https://w.cerebration.org/fahadshah.html

21. Vidal, Marta. “Kashmiris Turn to Art to Challenge

Indian Rule.” Al Jazeera, March 20, 2018. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2018/3/20/kashmiris-turn-to-art-to-challenge-indian-rule

[1] T. Housen, A. Lenglet, C. Ariti, S. Shah, H. Shah, S. Ara, K. Viney, S. Janes, and G. Pintaldi, “Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the Kashmir Valley,” BMJ Global Health 2, no. 4 (2017): e000419, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000419.

[2] S. Shoib, R. Mushtaq, S. Jeelani, J. Ahmad, M. M. Dar, and T. Shah, “Recent Trends in the Sociodemographic, Clinical Profile and Psychiatric Comorbidity Associated with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Study from Kashmir, India,” Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research (JCDR) 8, no. 4 (2014): WC01–WC06, https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/7885.4282.

[3] Kendra Cherry, “Identity vs. Role Confusion in Psychosocial Development,” Verywell Mind, updated December 4, 2023, https://www.verywellmind.com/identity-versus-confusion-2795735.

[4] Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose, “Identity Development Theory,” in Adolescent Psychology (Hudson Valley Community College), Lumen Learning, https://courses.lumenlearning.com/adolescent/chapter/identity-development-theory/.

[5] T. A. Klimstra, W. W. Hale III, Q. A. Raaijmakers, S. J. Branje, and W. H. Meeus, “Identity Formation in Adolescence: Change or Stability?” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 39, no. 2 (2010): 150–62, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9401-4.

[6] S. McKeown, D. Cavdar, and L. K. Taylor, “Youth Identity, Peace and Conflict: Insights from Conflict and Diverse Settings,” in Children and Peace, ed. N. Balvin and D. J. Christie, Peace Psychology Book Series (Cham: Springer, 2020), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22176-8_12.

[7] Laraib Malik, “Psychological Impacts of Conflict: Case Study of Kashmiri Women,” KIIR, Psychological Impacts of Conflict: Case Study of Kashmiri Women, accessed August 16, 2025, https://www.kiir.org.pk/Research-Paper/psychological-impacts-of-conflict-case-study-of-kashmiri-women-4472.

[8] Shoib et al., “Recent Trends in PTSD in Kashmir,” WC03.

[9] Lucia Ardovini, “Social Theory: Frantz Fanon,” SEPAD, July 5, 2022, https://www.sepad.org.uk/announcement/social-theory-frantz-fanon

[10] Ella Fincken, “The Legacy of Otherness in the Postcolonial World,” Arcadia, November 27, 2022, https://www.byarcadia.org/post/the-legacy-of-otherness-in-the-postcolonial-world.

[11] Talha AlAli, “Edward Said’s Perspective on Culture, Identity, and Mental Health,” decolonised minds, January 17, 2025, https://decolonisedminds.ie/edward-saids-perspective-on-culture-identity-and-mental-health.

[12] A. A. Dar and S. Deb, “Prevalence of Trauma Among Young Adults Exposed to Stressful Events of Armed Conflicts in South Asia: Experiences from Kashmir,” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 14, no. 4 (2022): 633–41, https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001045.

[13] S. Amin and A. W. Khan, “Life in Conflict: Characteristics of Depression in Kashmir,” International Journal of Health Sciences 3, no. 2 (2009): 213–23, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3068807/.

[14] Housen et al., “Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression and PTSD,” e000419.

[15] Ekta Oza, “Childhoods under Military Occupation: Everyday Experiences and ‘Insistence on Existence’ as Resistance in Kashmir,” Settler Colonial Studies 15, no. 2 (2024): 361–86, https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2024.2426111.

[16] Reddit user KashmiriCulture, “Imitation Over Identity: Our Cultural Decline,” r/Kashmiri, posted June 5, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/Kashmiri/comments/1i5q994/imitation_over_identity_our_cultural_decline/

[17] Sanjay Pandita, “The Kashmiri Youth between Legacy and Login,” Rising Kashmir, April 14, 2025, https://risingkashmir.com/the-kashmiri-youth-between-legacy-and-login/

[18] Arsalan Bukhari, “Young People Self-Medicate as Kashmir’s Mental Health System Fails Them,” Health Policy Watch, June 3, 2025, https://healthpolicy-watch.news/young-people-self-medicate-as-kashmirs-mental-health-system-fails-them/

[19] Aabid Bashir, Erum Batool, Tanya Bhatia, Sheikh Shoib, Nisar A. Mir, Uzma Bashir, Ruchita Singh, Margaret McDonald, Mary E. Hawk, and Sameer Deshpande, “Community Practices as Coping Mechanisms for Mental Health in Kashmir,” Social Work in Mental Health 21, no. 4 (2023): 406–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2022.2159779

[20] Mushtaq Ahmad Bhat and Jyoti Joshi, “Impact of Unemployment on the Mental Health of Youth in the Kashmir Valley,” Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy 10 (2020): 373, https://doi.org/10.35248/2161-0487.20.10.373

[21] Ruth Susan Mathew, “The Rap of Kashmir: Hidden Transcripts of Oppositional Resistance,” IIS University Journal of Arts 10, no. 2 (2021): 107–20, https://iisjoa.org/sites/default/files/iisjoa/Dec%202021/11.pdf

[22] Fahad Shah, “Resistance and Express: Art in the Valley of Kashmir,” Cerebration, accessed August 23, 2025, https://w.cerebration.org/fahadshah.html

[23] Marta Vidal, “Kashmiris Turn to Art to Challenge Indian Rule,” Al Jazeera, March 20, 2018, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2018/3/20/kashmiris-turn-to-art-to-challenge-indian-rule

Related Research Papers