THE FORGOTTEN PLIGHT OF KASHMIR’S SILENT SUFFERERS: WIDOWS AND HALF-WIDOWS

THE FORGOTTEN PLIGHT OF KASHMIR’S SILENT SUFFERERS: WIDOWS AND HALF-WIDOWS

Abstract

This article examines the struggles of widows and half-widows in Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK), with a focus on their social, economic, psychological, and legal challenges. Half-widows, whose husbands have disappeared but not been declared dead, face unique hardships that distinguish their experiences from those of widows. Drawing on reports, case studies, documentaries, and webinars, the study highlights how enforced disappearances, legal ambiguity, and lack of recognition deepen their marginalization.

The role of human rights activists and organizations, such as the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), is discussed in advocating for justice and documenting disappearances. By comparing the lives of widows and half-widows, the article underscores the gendered nature of conflict in Kashmir and calls attention to the need for political and legal reforms to address their pligh

By: Momina Farooq Khan

1. Introduction

Peace and conflict are enduring social realities, reflecting human tendencies toward harmony through cooperation and contention through rivalry. Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) explores these dynamics, defining peace not merely as the absence of war (negative peace) but as the presence of fairness, stability, access to resources, and protection from harm (positive peace).

Conflict, conversely, often rooted in struggles over power, resources, or identity, can escalate into structural violence such as poverty, displacement, and broken communities.12Johan Galtung’s “Mini Theory of Peace” frames conflict as a cycle of contradictions that fuel hostile attitudes and behaviours, perpetuating structural and direct violence with lasting physical, mental, and social consequences.3

In armed conflicts, women face disproportionate burdens, intensified by gender inequalities and patriarchal norms. They endure heightened risks of gender-based violence, forced displacement, and denial of basic rights, with sexual violence often weaponized to destabilize communities.

Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK), once called “paradise on earth” but now among the world’s most heavily militarized regions, exemplifies this reality. Since the 1947 partition, with tensions escalating after the contested 1987 state elections, the region’s conflict has involved extensive military presence and laws like the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, linked to enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings. These measures have left many women as widows, whose husbands are confirmed dead, or half-widows, whose husbands remain missing and undeclared deceased, trapping them in prolonged uncertainty.45

This study explores the challenges faced

by widows and half-widows in Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK) and how do they

survive during this prolonged conflict. Using qualitative data, it applies a Feminist Human Security Approach, as

articulated by Betty Reardon and Asha Hans in

the Gender Imperative: Human Security vs State Security 6 and Galtung’s

Mini Theory of Peace to

prioritize women’s safety and well-being, highlighting how violence cycles

1 Johan Galtung, “A Mini Theory

of Peace,” Transnational (January 4, 2007), accessed (August

13, 2025), https://www.oldsite.transnational.org/Resources_Treasures/2007/Galtung_MiniTheory.html

2

Heena Qadir, “Social Issues of

Widows and Half-Widows of Political Conflict: A Study in

Anantnag District of Jammu and Kashmir,” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science

Research 3, no. 10 (October

2017): 6–12, accessed (August 13, 2025), https://www.socialsciencejournal.in/assets/archives/2017/vol3issue10/3-7-14-

3 Johan Galtung, “A Mini Theory

of Peace,” Transnational (January 4, 2007), accessed (August

13, 2025), https://www.oldsite.transnational.org/Resources_Treasures/2007/Galtung_MiniTheory.html

4 Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), “Half Widow,

Half Wife? Responding to Gendered Violence in Kashmir” (Srinagar: Jammu and

Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, July 2011), 53 pages, accessed (August 13, 2025), https://jkccs.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/half-widow-half-wife-apdp-report.pdf

5 Farah Qayoom, “Women and Armed Conflict: Widows

in Kashmir,” International Journal of Sociology

and Anthropology 6, no. 5 (May 2014): 161–68, accessed (August 13, 2025)

https://academicjournals.org/article/article1397811777_Qayoom.pdf

6 Betty Reardon, “Women and Human Security: A Feminist Framework

and Critique of the Prevailing Patriarchal Security System,” in The Gender Imperative: Human

Security vs. State Security (Routledge, 2010), 10.

deepen trauma, especially for half-widows. It hypothesizes that systemic militarization and patriarchal structures in IIOJK exacerbate the marginalization of these women, limiting their access to resources and justice. The research addresses gaps in South Asian gender and conflict studies to propose policies for women in conflict zones.

2.

Historical and Political Background:-

Kashmir, located at the crossroads of Pakistan, India, and China, with the Himalayas running through it, has long been called “paradise on Earth” for its stunning beauty. During British colonial rule, its strategic location, mild climate, and rich resources made it a valued region. After the 1947 partition divided India and Pakistan, Kashmir became a major source of conflict between the two nations. Both claimed the region, leading to ongoing tensions. Into the 1970s and early 1980s, Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK) thrived as a tourist destination, drawing visitors to its lush landscapes. However, beneath the scenic beauty, political disputes simmered, setting the stage for unrest as Kashmiris grew frustrated with Indian governance.7

2.1 Rise of Conflict:-

In the 1980s, resentment against corruption and unfair elections under Indian rule fuelled a rise in secessionist sentiments among Kashmiri Muslims. The 1987 state elections, widely seen as rigged, marked a turning point, sparking public anger and resistance. By 1989, freedom fighters were active across IIOJK, pushing for freedom from Indian control. By 1991, the region faced a major uprising, nearly a full-scale insurrection. In the mid-1990s, the secessionist movement split into two main groups: one seeking complete independence from both India and Pakistan, and another wanting Kashmir to join Pakistan or become an Islamic state with ties to Pakistan. United against perceived Indian oppression, these groups sought freedom from draconian governance, reflecting diverse Kashmiri aspirations.8

2.2 Militarization:-

India responded with heavy militarization in IIOJK, deploying an estimated 500,000–1,000,000 troops, though exact numbers remain unclear. Special laws, including the Disturbed Areas Act, Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA), and Public Safety Act (PSA), gave the military broad powers. The AFSPA although established in 1958, applied to IIOJK in 1990 after it was declared a “disturbed area,” allowing for warrantless searches, arrests, and deadly force without accountability. These laws enabled the military to monitor communities closely, raid homes, and detain people without charges.9

2.3 Human Rights Violation:-

Militarization

led to widespread human rights abuses, including disappearances, killings, and

torture. Estimates suggest

over 70,000 deaths and 8,000 disappearances in two decades,

though IIOJK authorities report only 4,000 disappearances. A 2009

investigation uncovered nearly 3,000

bodies in unmarked graves across Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (IIOJK),

registered by Indian security forces as “foreign

militants” killed in “counter-insurgency

operations” and handed to local villagers for burial. However, local

residents and the International People’s

Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice in Kashmir (IPTK) disputed these

claims, identifying many as “fake

encounter” killings—extrajudicial executions of civilians, often in

custody, falsely recorded as armed confrontations initiated by the deceased.

IPTK’s examination of 50 cases labelled as “foreign militants” revealed that most were local Kashmiris, exposing the Indian government’s falsification of reports to perpetuate a narrative of external threats. This fabricated narrative serves to justify the heavy militarization in IIOJK, which has fuelled a largely non-violent secessionist movement seeking freedom from Indian oppression. 1011

2.4 Impact on Widows’

and Half-Widows:-

The lack of accountability in state courts, military tribunals, and human rights commissions has entrenched impunity, exacerbating the social, economic, and psychological burdens on widows and half-widows, leaving them to face stigma, trauma, and hardship without justice.

3.

Theoretical Framework

3.1 Key Concept:-

This study employs a Feminist

Human Security Approach

and Galtung’s Mini Theory

of Peace to examine the

different challenges of widows and half-widows in Indian-occupied Jammu and

Kashmir (IIOJK), centering women’s experiences in conflict.

3.2 Feminist Human Security

Approach:-

Betty Reardon and Asha Hans’ framework, from The Gender Imperative: Human Security vs. State Security, prioritizes human security over state security, emphasizing gender equality and non-violent conflict resolution. It defines security through four sources of well-being: a sustainable environment, fulfillment of basic needs (e.g., food, shelter), respect for dignity and identity, and protection from avoidable harm. In IIOJK, this approach reveals how militarization and patriarchal systems undermine women’s security, particularly for widows and half-widows facing violence, exclusion, and resource denial.1213

3.3 Johan Galtung’s Mini Theory of Peace:-

Johan Galtung’s theory distinguishes negative peace (absence of direct violence) from positive peace (absence of structural violence, with justice). It views conflict as cycles of contradictions, hostile attitudes, and violent behaviors.14 In IIOJK, this framework explains how militarization and oppressive laws perpetuate trauma and marginalization, especially for half-widows, guiding strategies for equitable solutions.

4.

Comparative Analysis

4.1. Social Challenges:-

In Kashmir, sexual violence has been weaponized as a strategy of war, deliberately used by the state to dominate, humiliate, and control communities. For women, particularly widows and half widows, this means carrying the double burden of personal grief and social exclusion. The absence of husbands leaves them dependent on in-laws or maternal families, yet instead of support they are often treated as burdens or symbols of misfortune. Those without shelter risk homelessness, while children are sometimes placed in orphanages, for example, those run by the Jammu and Kashmir Yateem Trust.15

Half widows face an especially cruel form of uncertainty. Their lives revolve around searching for their disappeared husbands, a process that forces them into courts, army camps, and police stations where they face harassment and humiliation. Ayesha (name changed) recalled being strip-searched at Central Jail despite the presence of metal detectors, even her infant daughter’s diaper being removed. Such treatment is intended not only to degrade but also to silence.

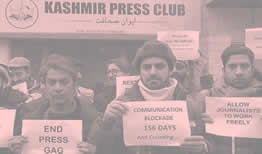

Authorities routinely deny knowledge of the missing, threaten women and their children, and create an atmosphere of fear.16 As Mushaal Hussein Mallick observed, even the glares of security officials can feel like acts of violence, breaking women’s dignity and confidence.17

Inside their own communities, half widows are often blamed for tragedy. They are accused of bringing misfortune to the family or suspected of immoral behavior. Asima from Baramulla described how people mocked her clothes at weddings, suggesting she was trying to attract men, until she stopped going out altogether. Some women are targeted by officials who exploit their vulnerability. Zara from Srinagar recounted how a government clerk suggested she provide sexual favors in exchange for financial relief. Others face pressure to remarry within their husband’s family to preserve inheritance, while some are seen as “women without men” and treated as socially dangerous.18

Widows, on the other hand, are condemned by traditional norms that label them as unlucky or responsible for their husband’s death. Activist Mohini Giri has described widowhood as a form of “social death,” where women are forced into deprivation, white clothing, and lifelong mourning. In Kashmir, these struggles intensify under poverty, militarization, and stigma. This form of exclusion is now referred to as “Widowism,” a term that describes the systematic marginalization of widows across South Asia.19

Despite these burdens, necessity has pushed many widows and half widows into new roles as breadwinners. Women who were once excluded from the workforce now sustain households and educate children. This reflects resilience, but it does not erase their pain. For most, widowhood and half widowhood remain unresolved states of grief, marked by exclusion, insecurity, and generational trauma.20

4.2. Economic Challenges

The death or disappearance of husbands’ forces women into economic responsibilities for which most were unprepared. Living as dependents all their lives, they suddenly become single parents who must provide food, shelter, and education for their children. The lack of education and skills pushes many into agriculture, menial jobs, or manual labor. These women are most often found in rural areas, where opportunities are scarce and survival depends on daily wages.

Social stigma adds to their burdens. Some in-laws blame widows for their sons’ deaths, while others, even if sympathetic, are unable to provide support. Relatives may abandon them altogether. Without access to property or inheritance, many women are left destitute.

Government assistance is extremely difficult to access, and when it is granted, it often becomes a conflict between half widows and in-laws who claim the majority share. Muslim Personal Law entitles them to only one-eighth of the relief or inheritance. Many women also resist accepting aid because they believe it is offered as a way to silence their legal struggles.21

The story of Meema Akhter, a half widow, illustrates this hardship. When her husband disappeared in 2007, she was left to raise four children alone. One of her child studies in an orphanage while the others attend government schools. To pay for their expenses, she sometimes cleans cow-sheds for a few rupees. “Life without my husband is very hard,” she says, “and now that my children are growing up, they need their father more than ever.” 22

Similarly, Tahira Bano, another half-widow, had to become the sole provider for her two sons, working as a tailor and beautician from a rented space funded by loans. Because of these pressures, widows and half widows are forced into new roles as workers and providers, reshaping family structures. Yet the burden remains heavy, and without education, property rights, or sustained support, their struggles continue across generations.

4.3. Psychological Challenges

Beyond economic hardship, the prolonged conflict has deeply scarred the minds and memories of widows and half widows. Living under constant militarization, they carry the fear of being raped, harassed, or humiliated both inside and outside their homes. The uncertainty of their husbands’ fate leaves them in a state of unresolved grief. Mothers often remain speechless when their children ask, “Mama, when will Baba come back?” Unable to answer, they live each day, each night, each minute, and each second with emotional wounds that never heal.24

Studies show that 36 percent of women in Kashmir suffer from anxiety disorders. Many live with trauma, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Nightmares, insomnia, and emotional numbness are common. Yet mental health services remain grossly inadequate. The Psychiatric Diseases Hospital in Srinagar receives hundreds of patients a day, yet doctors say half widows rarely come for treatment because they continue to hold on to hope. Instead, many self-medicate with easily available antidepressants, worsening their health.25

The case of Tahira Bano shows the depth of this suffering. After her husband disappeared, she developed severe insomnia and emotional detachment. She often surrounds herself with his old belongings, unable to let go of a past that remains unresolved. Reliant on medication, she struggles to cope with daily life. 26 Similarly, Rubina from Kupwara recalled that her mother-in- law wanted her to marry her husband’s youngest brother, who was only twelve years old. Asima from Baramulla refused proposals because she believed no stepfather would accept her children or love them the way their own father did.

Psychiatrists describe the mental state of half widows as “complicated grief.” This one-track focus on searching and waiting both sustains women and entrenches their suffering. For widows and half widows, the trauma is chronic, passed down across generations, making the conflict not only a physical war but also a psychological one.28

4.4. Legal Challenges

The legal framework in Kashmir further complicates the lives of widows and half widows. Widows may access some compensation or property rights, but half widows remain trapped in uncertainty. Without death certificates, they cannot claim inheritance, transfer property, or access state benefits. They are also barred from remarriage until their husbands are declared dead.

Under state law, this requires a wait of seven years, while Islamic interpretations vary widely. The Hanafi school historically required ninety years, though many modern Hanafi scholars have accepted shorter timeframes. The Maliki school allows remarriage after four to seven years if no information is found. Some women remarry with the approval of local qazis, especially those without children or with better economic stability. Salma from Uri explained that she was “lucky” to find a religious and kind husband and decided to give life a second chance.29

Still, social and cultural taboos around remarriage remain strong. Many half widows refuse remarriage either because they hope their husbands will return or because they fear a stepfather will mistreat their children. Legal exclusion also exposes them to exploitation. In-laws may deny them property rights, and remarriage often threatens the custody of their children. Psychiatrists argue that this legal limbo deepens psychological trauma.30

The words of many half widows capture this unresolved state:

“If my husband is alive, show me

his face. If he is dead, show me his grave so I can mourn properly.” Until

such closure is possible, both legally and emotionally, these half widows

remain trapped in limbo.31

4.5. APDP

In

1990, after the mysterious disappearance of her son, Parveena Ahanger, known as the Iron Lady of Kashmir, founded

the Association of Parents

of Disappeared Persons

(APDP). Since its creation, the APDP has documented at

least 1,500 cases of half widows in Kashmir. While most of these women are

wives of civilians, some are the wives of men labeled as “suspected militants.”

The families of the disappeared often narrate a similar pattern: security forces enter homes, take away the husband or eldest son for “questioning,” and the person is never returned. Relatives

30 Wave India, "In

Limbo: Kashmir's 'Half-Widows'," YouTube

video.

are sent from one camp to another, sometimes instructed to bring clothes for the missing man, only to be told later that he is not in custody.

APDP gives these families, especially women, a collective platform to voice their suffering. Through sit-ins, protests, and legal petitions, the organization highlights enforced disappearances as not merely a humanitarian tragedy but a political issue that demands truth and accountability.32

5.

Conclusion

The situation of widows and half-widows in Kashmir is not only a humanitarian concern but also deeply political. Dr. Ather Zia, in her discussion and webinar, explains that enforced disappearances must be understood in the context of Kashmir’s struggle for self-determination. She points out that while India presents itself internationally as the land of non-violence and democracy, the reality in Kashmir is one of continuous military violence and suppression since 1947. Democracy itself has been used as a weapon, with elections presented as proof of normalcy while the larger political dispute is denied. For half-widows, the denial of pensions, legal recognition, and basic rights reflects a wider effort to erase their suffering. 33

Dr. Zia stresses that the demand is not only for solidarity on human rights issues but also for solidarity with political rights. She argues that without the restoration of political rights, human rights violations will continue. Even if certain abuses stop, the central dispute will remain unresolved because the core of the struggle is the right to self-determination.

32 Free Press

Kashmir, “Widows of Kashmir,” YouTube video, 4:24, March 14, 2012 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WZ-Vwt4D_go&list=TLPQMjAwODIwMjUehefoD8vZCQ&index=12 33 Claire Bidwell,

“Kashmiri Half Widows – International Widows Day,” webinar.

7.

REFERENCES

· Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP). Half Widow, Half Wife? Responding to Gendered Violence in Kashmir. Srinagar: Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, July 2011. https://jkccs.wordpress.com/wp content/uploads/2017/05/half-widow-half-wife- apdp-report.pdf

·

Bidwell, Claire. Kashmiri Half Widows – International Widows Day. Webinar, YouTube, 1:24:30, June 11, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nFdGAa56_hI

·

Free Press Kashmir.

Widows of Kashmir. YouTube video, 4:24, March 14, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WZ- Vwt4D_go&list=TLPQMjAwODIwMjUehefoD8vZCQ&index=12

·

Galtung, Johan. A Mini Theory of Peace. Transnational, January 4, 2007. Accessed August 13, 2025.

https://www.oldsite.transnational.org/Resources_Treasures/2007/Galtung_MiniTheory.html

·

McLoughlin, Susan. Kashmir Through the Lens of a Feminist Human Security Approach: A Case

Study of Half-Widows. Master’s thesis, Utrecht University, July 28, 2023. https://studenttheses.uu.nl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12932/45211/McLoughlin_1193422_The sis.pdf

·

Mir, Rameez Raja. “Women and Violence: The Socio-economic and Political Status

of Half- Widows in Kashmir.” South Asia Journal, May 29, 2016. https://southasiajournal.net/women-and-violence-the-socio-economic-and-political-status-of- half-widows-in-kashmir/

·

Qadir, Heena. “Social Issues of Widows and Half-Widows of Political Conflict: A Study in Anantnag District of Jammu and Kashmir.”

International Journal

of Humanities and Social

Science Research 3, no. 10 (October 2017): 6–12. https://www.socialsciencejournal.in/assets/archives/2017/vol3issue10/3-7-14-554.pdf

·

Qayoom, Farah. “Women and Armed Conflict: Widows in Kashmir.”

International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology 6,

no. 5 (May 2014): 161–68. https://academicjournals.org/article/article1397811777_Qayoom.pdf

·

Reardon, Betty. “Women and Human Security: A

Feminist Framework and Critique of the Prevailing Patriarchal Security System.”

In The Gender Imperative: Human Security vs. State

Security, Routledge, 2010.

·

Real Stories. Kashmir’s Torture

Trail | Real Stories Full-Length Documentary. YouTube

video, 48:20, July 8, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hZ9anFMdcTI

·

South China Morning

Post. Where Is My Husband? After

19 Years, Woman

in Kashmir Still Seeks Answers from Indian

Government. YouTube video, 5:02, December 13, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QICfbMPJfUg&list=WL&index=2

·

VideoVolunteers.

How a ‘Half Widow’

of Kashmir Is Doing Menial

Jobs to Support

Her Family – Sajad Reports. YouTube video, 3:32, April 3, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=StBDJN_npKQ

·

Wave India. In Limbo:

Kashmir’s ‘Half-Widows’. YouTube video, 5:36, June 19, 2010. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mWibxZ8S8i4

Related Research Papers