The Cracks in the Concrete: Militarised Development and Kashmir’s Climate Crisis

The Cracks in the Concrete: Militarised Development and Kashmir’s Climate Crisis

A VALLEY ON THE BRINK

For decades, Kashmir has been framed through a security lens, driving infrastructure development focused on troop deployment rather than the well-being of its people. This militarised development is now exacerbating the region’s vulnerability to climate change, turning a fragile ecosystem into a disaster zone. Recent erratic weather, dry winters, devastating cloudbursts, and hail storms, aren’t merely natural events, but consequences of a development model imposed upon Kashmir. The stories from towns like Bijbehara and Shopian are symptomatic of a systemic disregard for the environment and livelihoods

Kishtwar, Shopian, Udhampur, Samba, and Anantnag led the gains.1 Yet the net loss weakens forest resilience. It reduces carbon absorption, increases emissions, and disrupts rainfall and temperature. Without urgent action to curb deforestation and manage fires, climate risks in Jammu and Kashmir will continue to rise, threatening both nature and communities. The monsoon season now brings more frequent and intense extreme weather. Cloudbursts and hailstorms are decimating orchards, the economic lifeline of many Kashmiri communities. On April 20, 2025, a devastating cloudburst struck Seri Bagna in Jammu and Kashmir’s Ramban district, killing three people, two children and a 75-year-old man. Incessant rainfall triggered flash floods and landslides that destroyed two houses in Bagahana village.

Between 200 to 250 houses were damaged, with Ramban town worst affected. In Dharamkund, 10 houses were completely destroyed and many others were partially damaged. The Srinagar-Jammu Highway was blocked at several points, leaving hundreds stranded. A large-scale rescue operation is ongoing.2 These disasters are linked to destabilised slopes, altered drainage, and the increased vulnerability of the landscape, all consequences of the infrastructure projects.

Construction itself degrades the environment. Blasting and excavation pollute the air and water, while haphazard waste disposal contaminates the soil. This development, ostensibly connecting Kashmir, disconnects it from its natural resilience.

In the name of development, the construction of underground tunnels and mega infrastructure like the Chenab Rail Bridge has pushed many villages in Jammu and Kashmir’s Reasi district into a severe water crisis. Perennial streams, once lifelines for local communities, have dried up following years of blasting, road cutting, and tunnel excavation. Anji stream, which served five villages, vanished after a railway tunnel project began, forcing residents to depend on water tankers or travel long distances to fetch water. Groundwater depletion has reached alarming levels, shrinking by nearly 60% in just seven years, due to underground tunneling and chemical seepage.

Kashmir. The mining process would also lead to deforestation, which results in increased carbon emissions, soil erosion, and habitat loss, further stressing the already fragile ecosystem. The mining byproducts could contaminate local water sources and fertile land, significantly damaging agriculture. The environmental damage could worsen land stability, leading to soil degradation and reduced agricultural productivity.4 This ecological harm would severely affect local communities, especially in places like Reasi, which rely on traditional farming. Finally, while the Indian government stands to gain economically, local communities will bear the brunt of the ecological and social consequences, with little to no benefit for them.

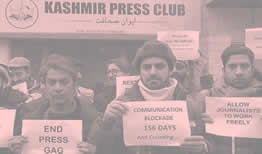

Critically, resources are diverted from sustainable initiatives. Investment in climate-resilient agriculture, water conservation, and renewable energy remains inadequate. Instead, the focus remains on control. This is particularly damaging given apple farming’s importance – supporting 3.5 million people and contributing over 8% to the region’s GDP. Farmers like Wamiq in Shopian articulate that losing their orchards is an existential threat. Resistance is growing. Reports detail government survey teams accompanied by police, silencing dissent. Protests in Shopian, where residents wore shrouds, and Anantnag demonstrate deep-seated anger. The lack of transparency – initial notifications via WhatsApp, land demarcation without notice – fuels distrust. MP Aga Ruhullah Mehdi highlighted in Parliament of India how the process violates the Land Acquisition Act of 2013, which mandates public consultation and impact assessments.

This resistance is compounded by political disenfranchisement. The revocation of Article 370 in 2019 and subsequent direct rule from New Delhi have created a democratic deficit. Projects are viewed as part of a broader agenda to alter the region’s demographics, exacerbated by a lack of accountability. As Michael Kugelman of the Wilson Center notes, projects once seen as innocuous are now viewed with suspicion, reflecting a deep distrust of the central government. The government’s response is often reactive, focusing on relief rather than addressing root causes. A systemic shift is needed – one prioritising ecological sustainability, community participation, and long-term resilience. This requires a moratorium on damaging projects until comprehensive, independent EIAs are conducted with genuine public involvement.

A commitment to reforestation with native species is essential, alongside investment in climate- resilient agriculture and water conservation. Crucially, a re-evaluation of development’s rationale is needed, moving away from a security-centric approach towards one prioritizing the needs and aspirations of the Kashmiri people. The increasingly erratic weather is a stark warning: Kashmir is paying a heavy price for a development model prioritising control over sustainability. Ignoring this will lead to further devastation. True security for Kashmir lies not in fortified infrastructure, but in a healthy environment and a resilient community – a community whose voices must be heard and respected. The fate of Kashmir’s apple orchards and the valley itself hangs in the balance

Related Research Papers