THE IMPACT OF DRACONIAN LAWS ON JOURNALIM IN OCCUPIED KASHMIR

THE IMPACT OF DRACONIAN LAWS ON JOURNALIM IN OCCUPIED KASHMIR

Abstract:

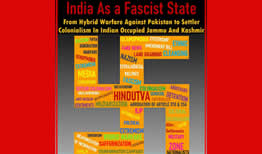

This study examines how draconian laws have reshaped journalism in Occupied Kashmir, particularly after the revocation of Article 370 in August 2019. Legal instruments such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), the Public Safety Act (PSA), and provisions of the Information Technology (IT) Act, along with practices like internet shutdowns and surveillance, have been widely used to restrict journalists.

These laws, framed under the pretext of maintaining security, are applied in vague and arbitrary ways, allowing authorities to detain or harass reporters for covering protests, human rights abuses, or dissenting voices. As a result, Kashmiri journalists face harassment, detention without trial, loss of professional freedom, and growing selfcensorship, while their families and communities also suffer the consequences. The paper highlights that these legal restrictions have not only silenced critical voices but have also undermined press freedom, public debate, and democratic accountability in the region. Drawing on Critical Legal Theory, the study argues that these laws function less as tools of justice and more as instruments of political control. The findings show that journalism in Kashmir now operates under fear and surveillance, creating a “media black hole” that deprives citizens of truthful information and weakens democracy itself.

TITLE: THE IMPACT OF DRACONIAN LAWS ON JOURNALIM IN OCCUPIED KASHMIR

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

Kashmir has remained one of the world’s most contested and conflict-ridden regions for decades. The area has been at the heart of political, territorial, and human struggles ever since the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. For the people living in the region, conflict has never been distant; it is woven into the everyday experience of militarization, surveillance, and restricted freedoms[1]. The events of August 2019 marked a turning point, when the Indian government revoked Article 370 of the Constitution, stripping Jammu and Kashmir of its limited autonomy.

BY: Sumaiya Kainat

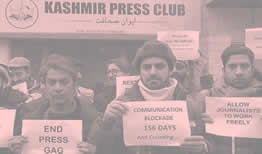

This sudden decision was accompanied by the deployment of additional troops, extended curfews, restrictions on assembly, and the suspension of internet and phone networks. The new order not only tightened the political control of the region but also reshaped the entire environment of communication and expression[2].Among the most deeply affected has been journalism. Reporters, editors, and photographers in Kashmir have long worked under pressure, but the removal of autonomy intensified the dangers attached to their profession.

Journalists face harassment, threats, arrests, and sometimes physical violence for performing their duties. Legal instruments such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and the Public Safety Act (PSA) give authorities wide powers to detain individuals without fair trial or due process, and these powers are often used against media workers[3]. Vague charges such as “antinational activity” or “threats to public order” allow the state to silence critical voices and discourage the reporting of sensitive issues such as protests, human rights abuses, or political dissent. Together with frequent internet shutdowns, digital surveillance, and censorship, these laws create an atmosphere where journalism becomes not only difficult but dangerous.

Press freedom holds immense value in any democratic society. Journalists are responsible for informing the public, holding those in power accountable, and amplifying the concerns of marginalized voices. In conflict zones like Kashmir, this responsibility becomes even more crucial because the outside world depends on journalists to understand realities that are otherwise hidden behind military and political barriers. When legal systems are used to intimidate or punish journalists, the result is a shrinking of civic space, a weakening of public debate, and a loss of transparency. Society is deprived of reliable information at the very moment it is needed most, and democratic accountability suffers.[4]

Literature review

Human rights organizations and press freedom mediums have repeatedly drawn attention to the declining state of media freedom in Kashmir. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) has described the region as a “media black hole” due to constant restrictions on information. Amnesty International has condemned the use of laws like UAPA and PSA, pointing out that they allow detention on vague grounds without sufficient legal safeguards. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has documented several cases where Kashmiri reporters were imprisoned or repeatedly summoned by police for their reporting, creating a culture of fear within the profession.[5] Human Rights Watch has criticized the use of internet blackouts and digital surveillance, which not only obstruct the work of journalists but also place them and their sources under constant risk.

Academic studies also confirm that censorship, harassment, and the absence of legal protection force many journalists into self-censorship, further narrowing the flow of information from the region. Beyond watchdog and academic reports, scholars have highlighted how the legal repression of journalism in Kashmir is connected to India’s broader policy of securitization in the region.

Studies emphasize that the framing of journalism as a “security threat” is not accidental but tied to state-building strategies, where control of narratives is as important as control of territory. This perspective adds depth to the argument that laws like UAPA and PSA are part of a systemic approach rather than isolated measures. Some comparative literature also situates Kashmir within a global context, showing how governments in conflict zones often deploy emergency laws to limit press freedom. Research on regions such as Palestine, Chechnya, and Xinjiang has drawn parallels with Kashmir, noting similar patterns of silencing dissent under the guise of counter-terrorism. These comparisons help to place Kashmir’s case within the broader debate about authoritarian legalism and the shrinking of civic spaces worldwide.

Other scholars argue that draconian laws in Kashmir not only impact journalists but also shape public opinion by curbing the flow of credible information[6]. This absence of balanced reporting enables misinformation and propaganda to dominate, reinforcing the official state narrative. By undermining independent journalism, these laws have a secondary effect of eroding trust between citizens and institutions, since people no longer feel they have access to impartial or truthful sources[7].

In addition, legal scholars have critiqued the vagueness of these laws as deliberate, pointing out that ambiguous language allows authorities wide discretion. Literature on international human rights law underlines that Kashmir’s laws often violate international standards on freedom of expression and due process. Reports by the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and regional rights groups emphasize that prolonged internet shutdowns, criminalization of reporting, and arbitrary detentions place India in violation of its international obligations.

Emerging literature focuses on the psychological and professional toll on journalists themselves. Qualitative studies based on interviews with Kashmiri reporters reveal that fear, anxiety, and constant uncertainty have become normalized experiences within the profession[8]. These works complement broader statistical reports by showing how repression is experienced at the individual and community levels, and how it alters the very culture of journalism in Kashmir[9].

Taken together, the reviewed literature demonstrates that repression of journalism in Kashmir is not an isolated or incidental occurrence[10]. It is rooted in systemic legal, political, and security frameworks that aim to silence dissent, restrict civic spaces, and reshape public discourse. However, while the existing scholarship provides valuable insights, there remains room for deeper analysis of how these mechanisms operate collectively and how they fit into the broader patterns of governance and control in conflict zones.

Despite this growing body of reports and studies, much of the available literature discusses press freedom as part of a larger human rights crisis. There is less focus on the exact role of specific laws in systematically repressing journalists.[11] What remains underexplored is how the legal framework itself is structured in a way that grants extraordinary powers to the state, enabling prolonged harassment of the media without judicial oversight. Another missing dimension is the theoretical understanding of how these practices relate to broader patterns of legal repression and the erosion of democratic freedoms. Addressing these gaps makes it possible to understand not only the outcomes arrests, censorship, fear but also the deeper mechanisms that produce them[12].

Theoretical

framework:

The theoretical framework guiding this study is Critical Legal Theory. This perspective argues that laws are not always neutral instruments of justice; rather, they are frequently designed and applied to preserve the interests of dominant groups and political authorities. In the case of Kashmir, laws such as UAPA and PSA appear to serve the purpose of national security, but in practice they have been used to suppress dissent and silence journalists. By doing so, they reveal how legal frameworks can be manipulated as tools of political control rather than impartial mechanisms of justice.

Through Critical Legal Theory, it becomes clear that restrictions on journalists in Kashmir are not isolated events or temporary responses to crises. Instead, they are part of a broader strategy to control narratives, manage dissent, and maintain political dominance. This framework allows us to see how law itself can become an instrument of repression rather than protection, and how its application undermines the very democratic values it claims to uphold. The repression of journalists in Kashmir is therefore not accidental but intentional a calculated use of legal mechanisms to shape political realities.

The application of Critical Legal Theory to this context also connects Kashmir’s situation with wider global patterns of repression. Across the world, governments have increasingly used the language of “national security” and “counter-terrorism” to justify shrinking civic spaces and silencing critical media. Kashmir becomes an acute case study where the consequences are immediate and visible: silenced voices, censored narratives, and a press corps forced into fear and compliance. This theoretical perspective is essential for understanding not only the lived experiences of Kashmiri journalists but also the broader consequences for democracy and human rights in conflict zones[13].

Kashmir’s story of media repression is, therefore, not only a regional issue but also a reflection of a larger global trend where laws and legal systems are used to shrink spaces of freedom. In Kashmir, the impact is immediate and visible: silenced voices, censored narratives, and a fearful press corp. By examining the mechanisms through which laws are applied against journalists and the consequences for press freedom and democracy, it becomes possible to see how conflict management and narrative control are pursued at the cost of fundamental rights[14].

CHAPTER 02: DRACONIAN LAWS, THEIR IMPACTS AND CHALLENGES

2.1 THE PRIMARY LEGAL

TOOLS (DRACONIAN LAWS) AGAINST JOURNALISTS IN OCCUPIED KASHMIR

The first step in understanding the repression of journalism in Occupied Kashmir is to examine the legal instruments most commonly employed against media professionals. These laws are not ordinary regulations of media practice; they are exceptional legal frameworks originally justified as tools for counter-terrorism and maintaining public order[15]. However, when applied to journalists, they become instruments of silencing, discouraging the coverage of dissent and human rights violations. The three most prominent frameworks are the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), the Public Safety Act (PSA), and certain provisions of the Information Technology (IT) Act, combined with routine administrative practices such as internet shutdowns and surveillance.

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA)

The UAPA is India’s central anti-terrorism law, amended several times to broaden its scope. The law allows authorities to declare individuals as “terrorists” even without a trial, and it permits detention for extended periods without formal charges. While its official aim is to combat terrorism, in Kashmir it has increasingly been used against journalists reporting on protests, security operations, or allegations of human rights abuses[16].

For journalists, the danger lies in the vague and broad definitions of unlawful activity. Phrases such as “supporting terrorism” or “threatening national integrity” can be interpreted to include critical reporting. For example, journalists who publish stories about civilian deaths during military operations may be accused of “glorifying terrorism” or “spreading anti-national sentiment.” This creates a climate of fear in which even factual reporting can be recast as criminal activity.[17

Highprofile cases

demonstrate this use. Reporters like Aasif Sultan and Irfan Mehraj have been

booked under UAPA for their reporting. The law allows the police to file a

First Information Report (FIR) and detain journalists for months, sometimes

years, before trials begin[18]. This long pre-trial

detention becomes the punishment itself. Even if a journalist is ultimately

acquitted, the chilling message is clear: covering sensitive topics can land

one in jail without resolution for years.

Thus, UAPA functions not only as a counter-terrorism tool but also as a mechanism for disciplining journalism, ensuring that reporters hesitate before covering stories that may embarrass authorities.

The Public Safety Act (PSA)

The PSA is another extraordinary law, specific to Jammu and Kashmir, which allows detention without trial for up to two years. Originally intended as a preventive detention law for maintaining public order, it has become infamous for its arbitrary application. Unlike regular criminal law, PSA allows the authorities to detain individuals based on suspicion alone, without the need to prove guilt in court[19].Journalists in Kashmir have repeatedly been detained under PSA for their reporting. The law is particularly dangerous for media workers because it bypasses judicial scrutiny. While normal criminal cases require evidence and judicial oversight, PSA authorizes administrative detention, meaning the decision to detain rests heavily on the police or district magistrates.

Several Kashmiri journalists have experienced PSA detention for articles that highlight issues like security force excesses, civilian casualties, or local protests. The law’s preventive logic detaining someone because they “may” disturb public order means that journalistic work critical of state policy can be criminalized before it even causes a reaction.[20] This creates an environment where self-censorship is a rational survival strategy. The PSA thus operates as a preemptive strike against dissent, preventing journalists from playing their democratic role by silencing them before their reporting reaches the wider public.

The Information Technology (IT) Act

The IT Act, especially provisions related to online content, has increasingly been used against Kashmiri journalists and media outlets[21]. Social media posts, online blogs, or digital reporting that challenge the government narrative can lead to legal complaints under the IT Act. For example, journalists posting updates about protests, clashes, or even health and humanitarian crises have faced police inquiries and charges. The significance of the IT Act in Kashmir is heightened by the central role of the internet in communication.

Because traditional media outlets face heavy restrictions, many journalists rely on online platforms to publish stories. Criminalizing online expression under the IT Act therefore restricts one of the last remaining avenues for independent voices.This law has also been combined with surveillance practices. Journalists’ phones and social media accounts are monitored, and “evidence” is often extracted from digital platforms to justify legal action. The IT Act, in effect, extends censorship from print and broadcast into the online world, where much of the present-day news circulation takes place.

Internet Shutdowns and Digital Surveillance

In addition to formal laws, administrative practices such as internet shutdowns and surveillance operate as indirect but powerful tools of control. Kashmir has been described as the world’s most internet-restricted region, with repeated blackouts since 2019.19 For journalists, internet shutdowns are devastating. They prevent timely reporting, disrupt fact-checking, and isolate reporters from sources. Even when the internet is partially restored, it often functions at reduced speeds, limiting the circulation of videos, photos, and live reporting.[23] This technological obstruction weakens the credibility and immediacy of Kashmiri journalism in the eyes of the global audience.

Surveillance adds another layer. Journalists report being summoned by police to explain their coverage, having their devices checked, and being warned against “anti-national” reporting. This constant monitoring fosters a climate of intimidation where journalists are aware they are being watched, pushing many to avoid sensitive subjects altogether.

The Combined Effect of Draconian Laws

Together, UAPA, PSA, IT Act provisions, internet shutdowns, and surveillance form a dense web of legal and administrative restrictions. Each law has its own logic counter-terrorism, public order, or digital regulation but in practice, they converge on the same outcome: silencing independent journalism[24]. This convergence ensures that journalists face a triple threat:

• Legal risk (arrest and detention),

• Technological barriers (internet blackouts), and

• Psychological intimidation (surveillance and harassment).

The combined effect is that journalism in Kashmir operates under conditions closer to emergency law than democratic normalcy. While officially justified in terms of security, these measures have become entrenched, turning exceptional restrictions into a routine part of daily reporting.

2.2. IMPACT ON JOURNALISTS’ LIVES, FREEDOM, AND SECURITY

The impact of draconian laws on Kashmiri journalists has been profound, reshaping not only how they work but also how they live their everyday lives. Reporting, which is supposed to be an act of documenting truth and informing the public, has instead become a high-risk activity. Many journalists describe working under a constant cloud of fear, where every article, photograph, or social media post could potentially lead to police interrogation or legal action.[25] The presence of laws like UAPA and PSA means that the risk is not hypothetical. Even a small story about civilian protests, human rights violations, or local grievances can be interpreted as “anti-national” or “supporting terrorism.”

This forces journalists into a dilemma: either pursue the truth and risk imprisonment or censor themselves to maintain safety.[26] One of the most visible impacts is the increase in self-censorship. Journalists admit that they avoid covering sensitive stories or alter their language to avoid angering authorities. Stories about military operations, human rights abuses, or public dissent are often toned down, left incomplete, or not reported at all24. This silencing effect is not imposed through formal bans alone; it is internalized by journalists who understand the risks of reporting too boldly. In this sense, the fear generated by draconian laws works as effectively as direct censorship.

The threat of arrest under UAPA or preventive detention under PSA can paralyze a newsroom, ensuring that only “safe” stories make it to publication. Beyond self-censorship, there are direct attacks on journalists’ freedom of movement and access. Reporters are frequently summoned by police, interrogated about their stories, and sometimes asked to reveal their sources. The constant monitoring of phones, laptops, and social media activity undermines basic principles of journalistic independence, especially the protection of confidential sources. When sources themselves know that journalists are being watched, they are less willing to share sensitive information, further restricting what can be reported. This surveillance-driven environment narrows the scope of journalism to such an extent that many reporters feel they can no longer perform their professional role with integrity[27].

The personal lives of journalists are also deeply affected. Arrests and detentions under UAPA or PSA do not only target the individual; they disrupt families, communities, and entire media outlets. The uncertainty of prolonged legal battles drains financial resources and damages reputations. For young journalists just starting their careers, the risk of being branded “anti-national” is enough to deter them from pursuing investigative stories altogether, pushing many into safer but less critical forms of reporting26. The psychological toll is immense. Many journalists describe feelings of helplessness, anxiety, and constant insecurity. Working under such conditions erodes the confidence needed to perform bold journalism, replacing it with fear and caution.

Physical safety has also become a serious concern. Journalists have been assaulted during protests, harassed while covering security operations, and subjected to raids at their homes or offices. The laws not only enable such treatment but also provide legal cover for it. Once a journalist is accused under a l like UAPA[28], they are often portrayed as a suspect rather than a professional carrying out legitimate work. This delegitimization makes them more vulnerable to abuse by both state actors and, at times, hostile segments of society. The stigma attached to being accused of

“terrorism” or “anti-national activity” can isolate journalists socially, adding to their vulnerability.

The broader impact is that journalism in Kashmir has been reduced to survival rather than free expression. The freedom to ask questions, to criticize, and to report independently has been undermined by a pervasive sense that the law is stacked against journalists[29]. Instead of acting as protectors of liberty, laws like UAPA and PSA have turned into instruments of fear. The message is clear: challenging the official narrative carries consequences, while compliance offers temporary safety. In such an environment, journalism no longer functions fully as a watchdog of power but instead struggles to simply exist. This undermines not only the individual freedom of journalists but also the collective right of society to access independent information.

2.3. IMPLICATIONS FOR PRESS FREEDOM AND DEMOCRACY

The use of draconian laws against journalists in Kashmir has consequences that extend far beyond the profession itself, shaping the entire ecosystem of public debate and democratic accountability. At its core, journalism functions as the bridge between citizens and the state, ensuring that the actions of those in power are subject to scrutiny[30]. When this bridge is weakened or dismantled, society loses one of its key mechanisms of oversight. In Kashmir, the application of laws such as UAPA, PSA, and the IT Act has narrowed press freedom to such an extent that public debate has become distorted, and the foundations of democratic accountability have been eroded.

The most immediate implication is the silencing of dissenting voices. Journalism thrives on diversity of opinion and the capacity to highlight issues from multiple perspectives. Yet in an environment where reporting critical of the government is equated with disloyalty or terrorism, only one version of reality the official narrative is allowed to dominate. This silencing deprives citizens of the full picture]. Reports of human rights violations, civilian hardships, or resistance movements rarely reach the broader public in their original, unfiltered form. Instead, the public conversation becomes increasingly shaped by state perspectives, while the experiences of ordinary Kashmiris are marginalized[32]. In democratic theory, free debate is supposed to allow citizens to make informed judgments. In practice, the curtailment of journalism in Kashmir makes informed judgment nearly impossible.

The repression of journalism also undermines trust in institutions. When citizens observe that journalists are being harassed or detained for performing their work, it signals that accountability is no longer valued. This erodes confidence in the judiciary, law enforcement, and political leadership. The perception that legal tools are being weaponized to silence critics fosters cynicism, suggesting that the state prioritizes control over justice[33]. Such a perception weakens the social contract, making citizens feel alienated from the structures that govern them. In fragile or conflict affected societies, this alienation can deepen existing tensions and fuel resentment, perpetuating instability rather than resolving it.

Another significant implication is the weakening of democratic checks and balances. A free press is often described as the “fourth estate,” essential for monitoring the other pillars of democracy. In Kashmir, the weakening of press freedom effectively removes this layer of oversight. Parliamentarians, courts, and civil society groups rely on journalists to uncover abuses, expose corruption, and track policy failures[34]. Without robust reporting, violations may go unnoticed, and accountability mechanisms become hollow. This allows state power to expand unchecked, creating conditions for authoritarian practices under the guise of maintaining law and order.

The impact also extends to the international stage. Kashmir has long been a subject of global concern, with governments, rights groups, and international organizations monitoring the situation. Independent journalism plays a crucial role in informing this global audience. However, when draconian laws restrict the flow of information, international actors receive a filtered narrative that may underplay or ignore human rights abuses[35].This complicates efforts to hold the state accountable at the global level, while giving authorities greater freedom to shape perceptions abroad. The result is that international diplomacy, advocacy, and intervention are weakened by the lack of reliable, independent reporting from the ground.

Equally important are the long-term social consequences of repressing journalism. Public debate in Kashmir has become narrower, more polarized, and less inclusive. Citizens are left without spaces where different viewpoints can be openly discussed[36]. When only state-approved narratives dominate, public frustration finds alternative, sometimes more radical, outlets. By closing off peaceful channels of expression, the repression of journalism risks pushing dissent underground, where it becomes harder to monitor and address constructively. In this way, silencing the press can paradoxically generate greater instability by eliminating peaceful avenues for criticism and dialogue[37].

Finally, the restriction of journalism weakens the very idea of democracy itself. Democracy is not only about elections or formal institutions; it is about the continuous circulation of ideas, criticisms, and accountability[38]. When journalists in Kashmir cannot operate freely, democratic values lose meaning on the ground. Citizens are deprived of their right to know, and governments face less pressure to justify their actions. Over time, this creates a hollow form of democracy institutions may remain, but their substance is undermined. The suppression of press freedom is therefore not just a media issue; it is a democratic crisis with implications for governance, rights, and peace[39].

CHAPTER 3: ANALYSIS AND

CONCLUSION

3.1 ANALYSIS

The preceding chapters have outlined the political context of Occupied Kashmir and identified the specific legal instruments used against journalists. This chapter moves beyond description and presents a critical analysis of how these laws function in practice, what their broader consequences are for journalism and society, and how they can be understood through the lens of Critical Legal Theory. The analysis shows that the suppression of journalism is not merely a side effect of conflict but a deliberate governance strategy that reshapes public discourse, democratic accountability, and the very meaning of rights in the region.

Law as an Instrument

of Power

A central insight from Critical Legal Theory is that law often reflects the interests of those who control political power rather than universal principles of justice. In Kashmir, this observation is highly relevant. The vague definitions and broad language of repressive laws are not accidental weaknesses but intentional features. They allow the state to blur the line between dissent and criminality, ensuring that journalism itself can be recast as a threat to security.

By transforming independent reporting into a punishable act, law becomes a tool not of neutrality but of domination. The legitimacy of these legal instruments lies in their appearance as counterterrorism measures, but their practical application reveals that they function primarily to control the flow of information. This transformation of law into a weapon of governance exemplifies how states can institutionalize repression under the guise of legality, leaving little room for challenge or accountability.

Fear, Self-Censorship,

and the Erosion of Agency

Perhaps the most significant consequence of these legal frameworks is not the number of journalists actually detained, but the culture of fear they produce. Detention without trial and prolonged interrogations send a clear signal to others: critical reporting is dangerous. As a result, many journalists retreat into silence or confine themselves to “safe” topics.

This widespread self-censorship marks a profound loss of agency. Journalism, by definition, is meant to question authority, document abuses, and give voice to marginalized communities. In Kashmir, however, the very instinct to ask questions has been stifled. Reporters calculate risks before publishing, families discourage investigative work, and younger journalists turn away from the profession entirely. This shift demonstrates how repression does not need to be constant or universal; the possibility of punishment alone is sufficient to produce silence. In this way, fear becomes as effective as formal censorship in narrowing the boundaries of public debate.

The Hollowing Out of

Democracy

Democracy is not sustained solely by elections or formal institutions. It also depends on a vibrant press that informs citizens and holds leaders accountable. In Kashmir, the weakening of journalism has hollowed out these democratic foundations. Institutions may still exist, but their functioning is undermined when citizens are deprived of independent information.

The dominance of the state narrative creates what has been described as a “information black hole.” Within this void, official accounts overshadow the lived realities of ordinary people. Reports of abuses, hardships, and dissent are buried, while government narratives present an image of order and progress. The result is a democracy that exists in name but not in practice. Citizens cannot make informed decisions, and accountability mechanisms lose their meaning when those in power are shielded from scrutiny. This hollowing out of democracy reveals that the suppression of journalism is not just a professional issue but a structural crisis that weakens governance itself.

Beyond Kashmir:

Broader Implications

The consequences of silencing journalism in Kashmir extend beyond the region. Internationally, India’s democratic image is undermined when independent voices are silenced. Governments, human rights organizations, and foreign publics depend on journalists for accurate accounts of conflict situations. By restricting this flow of information, the state not only suppresses local dissent but also shapes global perceptions in its favor. This manipulation makes it more difficult for international actors to apply pressure for reform, reinforcing the cycle of repression.

At the same time, silencing peaceful criticism risks fueling more radical forms of dissent. When people cannot express grievances through journalism or civic debate, they may turn to underground or violent means of resistance. In this sense, the repression of journalism may create the very instability that the laws claim to prevent. Kashmir thus illustrates a paradox: attempts to impose control through draconian laws can generate long-term insecurity rather than sustainable peace.

The situation also reflects a global trend in which states are increasingly using legal frameworks to shrink civic spaces. From internet shutdowns to digital surveillance, governments worldwide are adopting strategies that undermine press freedom. Kashmir becomes an extreme but instructive case study of how law, technology, and authoritarianism can converge to silence dissent.

Linking Findings to

Critical Legal Theory

The application of Critical Legal Theory helps to interpret these dynamics. The theory suggests that law is never neutral; it reflects power relations and is often designed to preserve authority rather than protect rights. In Kashmir, this is visible in how laws are written broadly, implemented selectively, and enforced arbitrarily. Such characteristics are not flaws to be corrected but deliberate mechanisms that serve the interests of the state.

Through this lens, the repression of journalism can be seen as part of a larger system of governance where law functions as a tool of narrative control. The legal system does not merely punish wrongdoing; it defines what counts as wrongdoing in the first place. By labeling reporting as “anti-national” or “terrorist activity,” the law reshapes social understanding of journalism itself. This shows how law can redefine social realities, ensuring that power is maintained not only through force but also through legitimacy derived from legal structures.

3.2 CONCLUSION

The study clearly shows that journalism in Occupied Kashmir is not functioning in a normal environment. Instead, it operates under heavy restrictions created by laws such as the UAPA, PSA, IT Act provisions, and practices like internet shutdowns and surveillance. These measures, which are presented as tools of national security, are actually being used as instruments of control. They make journalists vulnerable to arrest, harassment, and constant monitoring. The most concerning part is that these laws are written in such broad and vague language that almost any type of reporting can be declared “anti-national.” This has turned the simple act of telling the truth into a crime.

One of the most serious outcomes of this situation is the culture of fear that has spread among journalists. Even if every reporter is not arrested, the possibility of detention or harassment is always present. This makes many journalists hold back their words, avoid critical topics, or stop reporting on sensitive issues altogether. This process, known as self-censorship, damages the very spirit of journalism. Instead of being a profession that seeks truth and asks difficult questions, journalism in Kashmir has become about survival and playing safe. Families, careers, and futures are affected, as many young journalists feel discouraged from entering or continuing in this field.

The weakening of journalism has also weakened democracy in the region. A democratic system needs free media because it is through the press that citizens learn about injustices, hold leaders accountable, and form informed opinions. When journalists are silenced, the public is left with only the official version of events, while other realities remain hidden. This creates what has been called a “media black hole,” where information disappears and public debate shrinks. Institutions may continue to exist, but without independent journalism, they become hollow. Democracy in Kashmir now exists more in form than in substance.

The analysis also confirms the value of Critical Legal Theory in understanding the situation.This theory explains that laws are not always neutral or fair but are often shaped to serve those in power. The Kashmiri case is a strong example of this. The legal system is not simply failing to protect journalists; it has been designed and enforced in a way that deliberately targets them. By labeling reporting as “anti-national” or “terrorist activity,” the law changes how society views journalism itself. This shows that law is being used not only to punish individuals but also to control public narratives and shape collective memory.

Looking ahead, the consequences of these practices are very serious. If this cycle of repression continues, Kashmir will remain locked in silence, and the gap between the people and the state will continue to grow. Silencing journalists may seem to bring short-term control, but in reality, it creates long-term instability. When peaceful avenues of expression are blocked, frustration builds up and risks turning into unrest or radical forms of dissent. In this way, the suppression of journalism harms not just the media but the entire society.

Restoring press freedom in Kashmir is therefore not only a professional demand but a democratic necessity. The future of the region’s democracy depends on creating an environment where journalists can report freely without fear. This requires urgent reforms, such as revising or repealing the most repressive provisions of UAPA and PSA, ensuring proper judicial oversight of detentions, and ending the routine practice of internet shutdowns. These steps are essential to rebuild trust between the state and the people and to protect the citizens’ right to know the truth.

In short, what is at stake in Kashmir is not only the freedom of journalists but the health of democracy itself. A society without a free press is a society without accountability. True security cannot be achieved through silence and fear; it can only be built on transparency, justice, and truth. Journalism must be protected because it is the voice of the people, the guardian of democracy, and the bridge between citizens and the state. Ensuring press freedom in Kashmir is, therefore, not just about defending reporters it is about protecting the democratic rights of everyone living in the region.

Bibliography

Ahmad, Ishtiaq. Kashmir Dispute: An International Law Perspective. Islamabad: IPRI, 2020. Ahmad, Khalid. “Media and State Control in Kashmir: A Study of Human Rights Reporting.” Journal of Political Studies 27, no. 2 (2020): 145–162.

Ali, Zahid. “Media Freedom under Siege: Draconian Laws in Indian Occupied Kashmir.” Strategic Studies Journal 41, no. 1 (2021): 87–106.

Ahmad, Rashid. “The Role of Media in Highlighting Human Rights Abuses in Indian-Occupied Kashmir.” Journal of South Asian Studies 34, no. 2 (2019): 77–95.

Ali, S. M. “The Erosion of Press Freedom in Indian-Occupied Kashmir.” Pakistan Horizon 73, no. 3 (2020): 67–82.

Ashraf, Hina. “Freedom of Expression and Repression in Occupied Kashmir.” Pakistan Journal of International Affairs 4, no. 1 (2021): 33–49.

Amnesty International, “India: Repressive Media Policy in Jammu and Kashmir Must Be Immediately Withdrawn,” Amnesty International Press Release, July 2021,

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/07/india-repressive-media-policy-in-jammu-andkashmir-must-be-immediately-withdrawn/

Aziz, Khalid. “Kashmir’s Media Silence: Draconian Laws and Information Blackout.” Strategic Studies 40, no. 2 (2020): 112–130.

Baig, Adeel. “Digital Censorship and the Kashmir Conflict.” Pakistan Journal of Communication Studies 8, no. 1 (2021): 99–118.

Basit, Abdul. “Kashmir, Human Rights, and the Silencing of Journalists.” Journal of Political Studies 26, no. 1 (2019): 41–59.

Bashir, Uzma. “Media Blackouts and Human Rights Violations in Indian-Occupied Kashmir.” Journal of Contemporary Studies 9, no. 1 (2020): 89–106.

Bhat, Shazia. “The Silencing of Kashmiri Voices: A Study of Press Censorship.” Pakistan Journal of South Asian Studies 11, no. 2 (2021): 56–74.

Chaudhry, Sana. “Kashmir and Media Narratives: Human Rights under Siege.” Strategic Studies 41, no. 3 (2021): 145–164.

Farooq, Ayesha. “Media, Human Rights, and the Kashmir Dispute.” Pakistan Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies 4, no. 1 (2020): 25–42.

Hafeez, M. A. “Media Trials and Kashmir Conflict.” Journal of Security and Strategic Studies 13, no. 2 (2020): 73–90.

Hameed, Sadia. “Draconian Laws and Human Rights in Occupied Kashmir.” Journal of International Affairs 6, no. 1 (2020): 19–36.

Hashmi, Raza. “Media Crackdown in Indian-Occupied Kashmir.” Journal of South Asian Studies 35, no. 1 (2020): 115–132.

“India Batters Press Freedom and Journalists in Occupied Kashmir,” Dawn, January 23, 2022, https://www.dawn.com/news/1671052.

India Arrests Journalist in IIOJK for ‘Anti-National’ Posts,” The Express Tribune, February 5, 2022, https://tribune.com.pk/story/2342122/india-arrests-journalist-in-iiojk-for-anti-nationalposts

Iqbal, Salman. “Media Censorship and Draconian Laws in Kashmir.” Pakistan Journal of International Affairs 5, no. 2 (2021): 78–96.

Javed, Samina. “Occupied Kashmir and the Suppression of Media Freedoms.” Journal of Contemporary Affairs 7, no. 1 (2020): 54–72.

Kashmiri Journalist Granted Bail after 21 Months in Jail,” The Express Tribune, December 9, 2023, https://tribune.com.pk/story/2447247/kashmiri-journalist-granted-bail-after-21-months-injail

Khalid, Aroosa. “Human Rights Violations and the Media in Kashmir.” Journal of Political Science 30, no. 2 (2019): 133–151.

Khan, Adeel. “Information Blackout in Indian-Occupied Kashmir.” Strategic Studies 42, no. 2 (2021): 100–118.

Khan, Maryam. “Draconian Laws and Press Freedom in Kashmir.” Pakistan Journal of Peace Studies 12, no. 2 (2021): 61–79.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs Pakistan. Dossier on Human Rights Violations in IIOJK. Islamabad: MFA, 2022. https://mofa.gov.pk.

Mahmood, Taimur. “Censorship and Media Blackouts in Indian-Occupied Kashmir.” Journal of International Security Studies 8, no. 2 (2020): 43–61.

Malik, A. S. “The Impact of Repressive Laws on Journalism in Kashmir.” Pakistan Horizon 72, no. 4 (2019): 91–108.

Mehmood, Zahid. “Kashmir Conflict and the Media War.” Pakistan Journal of South Asian Studies 15, no. 1 (2020): 81–97.

Nadeem, Bushra. “Human Rights Abuses and the Silencing of Journalists in Kashmir.” Pakistan Journal of International Relations 3, no. 1 (2019): 29–47.

Naseer, Bilal. “Occupation, Oppression, and Media Silence in Kashmir.” Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies 5, no. 1 (2021): 52–70.

Qureshi, F. A. “Press Freedom and Human Rights in Indian-Occupied Kashmir.” Strategic Studies 43, no. 1 (2021): 134–152.

Rashid, Amina. “Media Blackouts and Human Rights in Kashmir.” Journal of Contemporary Studies 10, no. 1 (2021): 60–78.

Rehman, A. “Media Repression in Occupied Kashmir.” Pakistan Journal of International Affairs 6, no. 2 (2021): 41–59.

Saeed, A. H. “Kashmir Conflict and Information Control.” Pakistan Horizon 74, no. 2 (2021): 77–95.

Silenced, Surveilled, Subjugated,” The News International, August 2025, https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/1332317-silenced-surveilled-subjugated Shah, Nida. “The Silencing of Media in Indian-Occupied Kashmir.” Journal of Security Studies 12, no. 2 (2020): 88–106.

Tariq, Hamza. “Journalism under Siege: The Case of Kashmir.” Pakistan Journal of Political Studies 29, no. 1 (2019): 19–37.

Umar, Khadija. “Kashmir and the Politics of Silence.” Journal of Strategic Studies 45, no. 2 (2021): 120–138.

Usman, Fiza. “Press Censorship and Kashmir Dispute.” Pakistan Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies 6, no. 1 (2021): 39–57.

Wani, Shabir. “Freedom of Press in Indian-Occupied Kashmir.” Pakistan Journal of International Affairs 7, no. 1 (2022): 71–89.

Yousaf, Hira. “Media Suppression and Human Rights Violations in Kashmir.” Journal of Political Science 31, no. 1 (2020): 103–121.

Yousaf, Saad. “Censorship and the Shrinking Space for Journalism in Kashmir.” Journal of International Security Studies 9, no. 1 (2021): 83–101.

[1] Ayesha Khan, Media Under Siege: Reporting in Indian-Occupied Kashmir (Islamabad: Institute of Regional Studies, 2023).

[2] Huma Baqai, “Silencing Voices: Media Freedom in Kashmir under Indian Laws,” Strategic Studies 41, no. 2 (2021): 85–104.

[3] Muhammad Taqi, “Press Freedom and Human Rights in Indian-Occupied Kashmir,” Journal of Political Studies 29, no. 1 (2022): 45–62.

[4] Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILDAT), Human Rights and Freedom of Expression in Occupied Kashmir (Lahore: PILDAT, 2021).

[5] Rabia Akhtar, “Kashmir’s Gagged Media: Legal Repression and Journalistic Challenges,” Pakistan Horizon 75, no. 3 (2022): 67–84.

[6] Rabia Akhtar, “Kashmir’s Gagged Media: Legal Repression and Journalistic Challenges,” Pakistan Horizon 75, no. 3 (2022): 67–84.

[7] Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILDAT), Human Rights and Freedom of Expression in Occupied Kashmir (Lahore: PILDAT, 2021).

[8] Institute of Regional Studies (IRS), Media Under Siege: Reporting in Indian-Occupied Kashmir (Islamabad: IRS, 2023).

[9] Maheen Javed, “Psychological Toll of Fear: Journalists’ Experiences in Occupied Kashmir,” Pakistan Psych Journal 7, no. 3 (2024): 45–61.

[10] Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), Kashmir Media in Chains: Draconian Laws and the Suppression of Journalism (Islamabad: IPS Press, 2023).

[11] Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), Kashmir Media in Chains: Draconian Laws and the Suppression of Journalism (Islamabad: IPS Press, 2023).

[12] Saadia Khan, “Communication Blackouts and Press Restrictions in Occupied Kashmir,” Journal of Contemporary Studies 10, no. 2 (2021): 133–150.

[13] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Pakistan, Human Rights in Indian-Occupied Jammu & Kashmir: Dossier 2022 (Islamabad: MOFA, 2022).

[14] Fatima Ali, “From Curfew to Crackdown: Press Freedom after the Revocation of Article 370,” Journal of South Asian Affairs 12, no. 4 (2023): 101–120.

[15] Zahid Mahmood, “Arbitrary Detentions under PSA in Kashmir,” Human Rights Journal 18, no. 1 (2022): 23–38.

[16] Freedom Network Pakistan, Silenced Tweets: Analysis of IT-Act Cases Against Kashmiri Journalists (Islamabad:

FNP, 2023

[17] Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), Under Digital Siege: Internet Shutdowns and Press Freedom in IIOJK (Islamabad: HRCP, 2024).

[18] PPF, “Media Watch: UAPA FIRs Against Kashmiri Reporters in 2022,” PPF Alerts (Islamabad, January 2023), https://pakistanpressfoundation.org/... (accessed July 10, 2025).

[19] KIIR, Media Blackouts and Human Rights: A Kashmir Case Study (Islamabad: KIIR, 2023)

[20] Shireen Ahmed, “Censorship by Law: The IT Act and Journalistic Self-Censorship in Kashmir,” Pakistan Legal Review 5, no. 2 (2022): 64–89.

[21] Zafar Iqbal, Danger, Detention, Dissent: Lives of Kashmiri Journalists (Lahore: Beacon Publications, 2024).

[22] Amina Butt, “Press Freedom in Conflict Zones: Lessons from IIOJK,” Strategic Perspective 8, no. 3 (2023): 55–73. 19 Ministry of Human Rights, Government of Pakistan, Annual Report 2023–24: Human Rights Violations in Occupied Kashmir (Islamabad: MoHR, 2025).

[23] Zahra Siddiqui, “Preventive Detention and the PSA: Legal Framework and Press Repercussions,” South Asian Legal Studies 3, no. 1 (2022): 14–37.

[24] Amir Raza, State Power and the Silencing of Media: Kashmir 2019–2023 (Islamabad: National Institute of Policy Studies, 2024).

[25] Rashid Khan, “Internet Shutdowns as a Tool of Control: Impact on Investigative Journalism in Kashmir,” Media & Conflict Quarterly 2, no. 4 (2022): 89–106.

[26] HRCP, Civic Space Eroded: Press Freedom and Human Rights in Pakistan and IIOJK (Islamabad: HRCP, 2025). 24 Aliya Khan, “Legal Ambiguity and ‘Anti-National’ Narratives: Reporting Kashmir under UAPA,” Journal of Law and Society 11, no. 2 (2023): 134–152.

[27] PILDAT, Dismantled Autonomy: Political and Legal Suppression of Media in Kashmir (Lahore: PILDAT, 2023). 26 Maheen Javed, “Psychological Toll of Fear: Journalists’ Experiences in Occupied Kashmir,” Pakistan Psych Journal 7, no. 3 (2024): 45–61.

[28] Iqra Shah, “Press as ‘Threat to Security’: UAPA and the Criminalization of Journalism,” Pakistan Security Review 9, no. 2 (2022): 98–115.

[29] KIIR, “Detention without Trial: Patterns of PSA and UAPA Use against Journalists,” KIIR Policy Brief (Islamabad, 2024)

[30] Nasir Khan, Broken Lines: Communication Barriers and Press in Kashmir (Islamabad: Media Freedom Trust, 2022).

[31] PPF, Media Freedom Alert: Digital Repression in Occupied Kashmir (Islamabad: PPF, 2024).

[32] Samina Rahman, “State Narratives and Silencing Dissent: A Study of Press Coverage in IIOJK,” Critical Asian Studies Journal 14, no. 1 (2023): 18–35.

[33] Ministry of Information, Government of Pakistan, Report on Media Suppression in Kashmir (2025) (Islamabad:

MoI, 2025).

[34] Sara Malik, “Fear Equals Silence: Self-Censorship by Kashmiri Journalists,” South Asia Media Watch 6, no. 2 (2024): 77–92.

[35] Freedom Network Pakistan, Annual Press Freedom Index 2024: Pakistan & IIOJK (Islamabad: FNP, 2025).

[36] Qasim Ahmad, Between Armed Forces and Arrests: Journalists in Kashmir (Lahore: Frontier Publishers, 2023).

[37] HRCP, “Surveillance and Intimidation: The Reality for Journalists in Kashmir,” HRCP Press Statement (Islamabad, March 2025).

[38] Ayesha Zahra, “Journalistic Integrity in the Shadow of Detention: Personal Accounts from Kashmir,” Asian Journalism Studies 15, no. 4 (2023): 210–227.

[39] HRCP, Between Law and Fear: Journalists’ Rights under PSA and UAPA in IIOJK (Islamabad: HRCP, 2024).

Related Research Papers